|

OUR

AMERICAN

REVOLUTION

ANCESTORS

PRINT Version

of this article

National Society of the

Sons of the American Revolution

Back to

Lineage from

Col. Nicholas Lewis

Col. Nicholas

Lewis

m. Mary Walker

Jane Walker

Lewis

m. Hudson Martin

Mary Walker

Martin

m. Thurston Dickinson

Frances Elizabeth Dickinson

m. John Duggins

Elizabeth Marshall Duggins

m. James Henry Smith

Laura Ann Smith

m. Peter Christian Jensen

Lucile Marguerite Jensen

m. Wilhelm A. Heineman

Peter E. Heineman

m. Doris

J. Crum

Peter L.

Heineman

Lineage

from

Dr. Thomas Walker

Dr. Thomas

Walker

m. Mildred Meriwether

Mary Walker

m. Col. Nicholas Lewis

Jane Walker

Lewis

m. Hudson Martin

Mary Walker

Martin

m. Thurston Dickinson

Frances Elizabeth Dickinson

m. John Duggins

Elizabeth Marshall Duggins

m. James Henry Smith

Laura Ann Smith

m. Peter Christian Jensen

Lucile Marguerite Jensen

m. Wilhelm A. Heineman

Peter E. Heineman

m. Doris

J. Crum

Peter L.

Heineman

Lineage

from

Lt. Hudson Martin

Lt. Hudson

Martin

m. Jane Walker Lewis

Mary Walker

Martin

m. Thurston Dickinson

Frances Elizabeth Dickinson

m. John Duggins

Elizabeth Marshall Duggins

m. James Henry Smith

Laura Ann Smith

m. Peter Christian Jensen

Lucile Marguerite Jensen

m. Wilhelm A. Heineman

Peter E. Heineman

m. Doris

J. Crum

Peter L.

Heineman

Lineage

from

Pvt. William T. Duggins

William T. Duggins

m. Elizabeth Perkins

John Duggins

m. Frances E. Dickinson

Elizabeth Marshall Duggins

m. James Henry Smith

Laura Ann Smith

m. Peter Christian Jensen

Lucile Marguerite Jensen

m. Wilhelm A. Heineman

Peter E. Heineman

m. Doris

J. Crum

Peter L.

Heineman |

INTRODUCTION

The American Revolution

was a political movement during the last half of the 18th

century that resulted in the creation of a new nation in 1776,

the United States of America, and ended British control of the

Thirteen Colonies. In this period, the Colonies rebelled and

entered into the American Revolutionary War against the British

between 1775 and 1783, which culminated in an American

declaration of independence in 1776 and an allied victory. The

French government, army, and navy played critical roles in

aiding the newfound Americans financially and in providing

direct military and naval support.

The

Revolution involved a series of broad intellectual and social

shifts that occurred in the early American society, such as the

new republican ideals that took hold in the American population.

In some states sharp political debates broke out over the role

of democracy in government. The American shift to republicanism,

as well as the gradually expanding democracy, caused an upheaval

of the traditional social hierarchy, and created the ethic that

formed the core of American political values.

The

revolutionary era began in 1763, when Britain defeated France in

the French and Indian War and the military threat to the

colonies from France ended. Britain imposed a series of taxes

which the colonists thought were illegal. After protests in

Boston the British sent combat troops, the Americans trained

militiamen and fighting began in 1775. The climax of the

Revolution came in 1776, with the signing of the Declaration of

Independence. The end of the Revolutionary War is marked by the

Treaty of Paris in 1783, with the recognition of the United

States as an independent nation.

This publication is

not a retelling of the history of the American Revolution. It

is the biographies of four Revolutionary War ancestors; Col.

Nicholas Lewis, Lt. Hudson Martin, Dr. Thomas Walker, and Pvt.

William T. Duggins.

Col.

Nicholas Lewis

Nicholas Lewis Nicholas was born in

"Belvoir" Louisa Co., Virginia on January 19, 1734.

He was the second son of Col. Robert

Lewis of Belvior and Jane Meriwether. Robert was the third son

of Col. John Lewis and Elizabeth Warner. He was born at Warner

Hall, Gloucester County in 1702. He married Jane Meriwether in

1725. They had 11 children.

-

JOHN LEWIS, b. August 31, 1725, Of

Halifax, Virginia.; d. 1787, Caswell, N.C..

-

JANE LEWIS, b. January 01, 1726/27, New

Kent Co., Virginia.; d. Abt. 1794, Pittsylvania, Virginia..

-

COL. NICHOLAS LEWIS, b. January

19, 1734, "Belvoir" Louisa Co., Virginia., Virginia.; d.

December 08, 1808, "The Farm", Albemarle Co., Virginia..

-

COL.

WILLIAM LEWIS, b. Abt. 1730, Locust Hill, Albemarle Co.,

Virginia.; d. November 14, 1779, "Cloverfield, " Albemarle,

Virginia..

-

CHARLES LEWIS, b. 1730, of North Garden,

Louisa Co., Virginia.; d. 1779, Albemarle Co., Virginia..

-

MARY LEWIS, b. Abt. 1735, Albemarle Co.,

Virginia.; d. May 31, 1812, Albemarle Co., Virginia..

-

MILDRED LEWIS, b. September 01, 1737,

"Belvoir", Albemarle Co., Virginia.; d. Abt. 1825.

-

ROBERT LEWIS, b. 1738, Of Halifax,

Virginia.; d. 1780, Greenville Co., N. C..

-

ANN LEWIS, b. Abt. 1742, Of "Belvoir"

Albemarle, Virginia.; d. Abt. 1769, Spotsylvania, Virginia..

-

SARAH LEWIS, b. 1748, Albemarle,

Virginia..

-

ELIZABETH LEWIS, b. 1750, Hanover Co.,

Virginia.; d. 1833.

In 1735, Nicholas

Meriwether, Nicholas’ grandfather, obtained patents from King

George III to approximately 19,000 acres in Albemarle County

east of Charlottesville. One parcel of 1020 acres was located

west of the Rivanna River, the area which now is the Locust

Grove and Belmont neighborhoods. It became known as “The Farm”

because it was the one cleared area in a virgin forest. A

building on the property likely served as headquarters for

British Col. Banastre Tarleton briefly in June 1781. In

1825, Charlottesville lawyer and later University of

Virginia law professor, John A. G. Davis purchased a

portion of the original tract and engage Thomas

Jefferson’s workmen to design and build this house. It

is considered one of the best surviving examples of

Jeffersonian residential architecture. Maj. Gen. George

A. Custer occupied the house as his headquarters for a

brief time in March 1865.

|

|

A main house and

out buildings were built at “The Farm” on the hill facing the

river to the east. The house burned after a couple of decades.

Nicholas Lewis, grandson of Meriwether, inherited the property

in 1762 and built another main house facing the river around

1770. It was described as a place of beauty surrounded by a

garden of roses, shrubs and fine fruit. It could have been built

on or near the foundations for the first house. A listing in The

Mutual Assurance Society of Virginia records from 1805 may

describe the house. It was a wooden dwelling two stories high,

48 feet long and 22 feet wide.

|

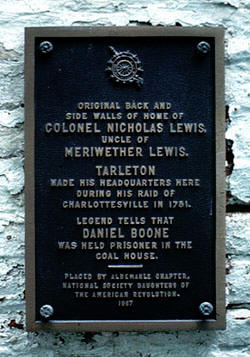

The 1770

house was constructed of pitsawn with mortise-and-tenon

joinery. It is in this house the British Col. Banastre

Tarleton made his headquarters when he arrived in

Charlottesville in 1781 in his futile attempt to capture

Thomas Jefferson. Tarleton was successful in capturing

Daniel Boone, who at that time was a member of the

Virginia legislature, and held him captive in Lewis'

house. Thomas Jefferson himself often visited the Lewis

house and regularly rode through the property on his way

to Charlottesville to visit the university he was

building. There is an active spring down the hill a

couple of hundred yards to the south. |

In 1825, Charlottesville

lawyer and later University of Virginia law professor, John A.

G. Davis, purchased a portion of the original tract and engaged

Thomas Jefferson's workmen to design and build this house. It is

considered one of the best surviving examples of Jeffersonian

residential architecture. Maj. Gen. George A. Custer occupied

the house as his headquarters for a brief time in March 1865.

All that

remains of "The Farm" is the kitchen or cook’s house. It is now

in the middle of a middle class housing subdivision facing

Twelfth Street. It is still surrounded by mature hardwood trees

and retains its view of Monticello.

Family

Nicholas Lewis married Mary (Capt. Molly)

Walker in 1758. Mary was the daughter of Dr. Thomas Walker and

Mildred Thornton Meriwether of Castle Hill where Mary was born

in 1742. Nicholas and Mary had 15 children:

-

JANE WALKER LEWIS, b. 1757; d. 1838.

-

MILDRED WALKER LEWIS, b. 1761; d. 1814.

-

THOMAS WALKER LEWIS, b. April 24, 1763,

Locust Grove, Albemarle, Virginia.; d. June 09, 1807,

Albemarle, Virginia..

-

MARY LEWIS, b. 1765.

-

NICHOLAS MERIWETHER LEWIS, b. August 18,

1767; d. September 22, 1818.

-

ELIZABETH LEWIS, b. June 06, 1769,

Albemarle, Virginia.; d. March 1842, Cloverfields,

Albemarle, Virginia..

-

ELIZABETH LEWIS, b. June 06, 1769,

Albemarle, Virginia.; d. March 1842, Cloverfields,

Albemarle, Virginia.; m. WILLIAM DOUGLAS MERIWETHER,

February 29, 1788, Goochland Co., Virginia.; b. November 02,

1761, Cloverfields, Albemarle, Virginia.; d. January 21,

1845, Albemarle, Virginia..

-

ALICE THORNTON LEWIS, b. 1771; d. Young.

-

ROBERT WARNER LEWIS, b. 1774.

-

FRANCES T. LEWIS, b. 1776; d. Young.

-

JOHN P. LEWIS, b. 1778; d. Young.

-

CHARLES LEWIS, b. 1783; d. Young.

-

CHARLES LEWIS, b. 1783; d. Young.

-

MARGARET LEWIS, b. 1785, "The Farm",

Albemarle Co., Virginia..

-

MARGARET LEWIS, b. 1785, "The Farm",

Albemarle Co., Virginia.; m. CHARLES LEWIS THOMAS

Changing Times

July, 1775, saw the Governor of Virginia a fugitive and the

members of the Assembly met as a Provincial Convention to raise

and embody an armed force to defend the Province. The flight of

the Governor left the Colony without an executive head and the

Convention therefore appointed, on the sixteenth of August, a

Committee of Safety of eleven members to continue until its next

session.

It was to carry into

execution all ordinances and resolutions of the Convention, to

grant commissions to all provincial military officers, to

appoint commissaries, paymasters and contractors and to provide

for the troops. It was to issue warrants on the Treasurer to

supply these agents with money and pay them for their services

and to settle such incidental expenses as arose in connection

with the military establishment. All public war stores were to

be in its charge. The Committee, moreover, was made

Commander-in-Chief of the forces of the Province, and every

officer, to the highest, was obliged to swear obedience to it.

If sufficient danger

threatened the Colony before the troops which the Convention had

determined upon could be raised and organized, the Committee

might call upon the volunteer companies which had already sprung

up through the Colony, to take the field. Col.

Nicholas Lewis was a Member of the Committee of Safety

and Convention of 1775.

The Committee was

directed to keep a journal and lay the account of its

proceedings before the Convention for inspection. Its members

were exempt from enlistment and could hold no

military office. A complete break with the royal government was

insisted upon, since no member of the Committee might fill any

position of profit under the Crown. Fifteen shillings a day

(which a later Convention reduced to ten) was the compensation

allowed the members.

By other acts of this

Convention an appeal to the Committee of Safety was allowed any

officer from the decision of a court-martial, and no sentence of

death given in such a court could be executed until the

Committee of Safety had given its approval.

The Convention adjourned

till the first of December, leaving the Committee of Safety in

charge. At the beginning of the next session, the Committee was

continued, and on December 16th, a new one appointed of the same

size, to sit until the Convention’s next session. The same

powers that the former body had enjoyed were given it, and

others added. Any person found aiding the enemy was liable to be

seized and imprisoned, and his estates confiscated by the

Committee, unless the latter saw fit to pardon him. Three men

were appointed to act as a Court of Admiralty, and in all cases

where the ship and cargo were condemned appeal was allowed to

the Committee of Safety. It was, moreover, directed to

commission five members from each of the county committees to

have jurisdiction over all persons suspected of enmity to the

State. It was to hear appeals from their decisions and its

sentence was to be final. If a slave was taken in arms against

the Colony or in possession of the enemy through his own choice,

he could be sent by the Committee to any of the French or

Spanish West Indies to be exchanged for war stores. If

circumstances rendered his transportation inconvenient it could

employ him in any way for the public service. Those inhabitants

who refused to take up arms in the American cause, provided they

had committed no act of hostility or enmity, might leave the

Colony, under a license from the Committee of Safety.

The last Provincial

Convention, the body that framed the new constitution of

Virginia, came together in May, 1776. It revived the

Committee of Safety, whose term expired with its meeting, and

continued it until its own dissolution on July 5th.

Although the Assembly

under the constitution was not to convene until fall, the

Convention elected the Governor and Privy Council to take charge

of the State till then and usher in the new regime. The need for

the Committee of Safety therefore, was taken away, and it passed

out of existence with the Convention.

The functions of the

Virginia Committee were, in brief, to commission the officers,

to command the troops, to appoint agents to equip and feed them,

to pay the military expenses of the State, to imprison its

hostile inhabitants, to hear appeals from the Admiralty Court,

from the County Courts of Inquiry and from Courts Martial.

Its powers were

extensive, controlling the military, and to a large extent the

financial resources of the Colony, but during its administration

no danger threatened Virginia sufficient to test the stability

of its authority or its capacity to deal with a crisis. Its work

during the year in which it was the executive of the Colony,

consisted merely in organizing the militia, in providing it with

necessaries and in sending troops to retaliate upon the

irritating incursions of Lord Dunmore. The greater part of the

inhabitants were Whigs and the orders of the Committee were

fulfilled without friction. Virginia was not, like New Jersey or

Pennsylvania, the scene of a conquering army, and the problems

that their Committees had to face were not presented. Neither

was it at any time obliged to assume the whole authority of the

State. The Convention was in session during much of the year,

and directed the Committee in various ways. Even during its

adjournments it was still in existence and could always be

brought together if sufficient danger threatened. The Committee

of Virginia therefore occupied a less responsible position than

the Councils of Safety of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, or of

Vermont.

The Committee led a busy

if not a stirring life. The actual work of procuring arms,

accoutrements and provisions was largely in the care of

commissaries and contractors chosen by it, but they were under

the direction of the Committee and responsible to it, and every

disbursement that was necessary to satisfy the wants of the

troops, even the most minute, passed through its hands.

Conservative and radical

elements clashed in Virginia as in Pennsylvania. The

disagreement was not sufficient to overthrow the existing

regime, but centering, as it did, around prominent

personalities, brought with it sufficient bitterness. Patrick

Henry, the leader of the radicals, had been appointed

Commander-in-Chief of the Virginia army by the Convention. At

the head of the Committee of Safety was Edmund Pendleton one of

the foremost conservatives. It would seem that Henry was, as a

matter of fact, a better orator than general. At all events his

military capacity was distrusted to such an extent by the

Committee of Safety that Colonel Woodford, a subordinate, but

more experienced officer was detailed by it to command the

expedition against Lord Dunmore. Opportunity for military

achievement was rare in Virginia then and Henry felt the task

should have been his. He resented the fact that Woodford

reported directly to the Committee and not to him and finally,

when the Committee ordered Henry to prepare for winter quarters,

it seemed it was purposely refusing him any opportunity of an

engagement before the Virginia troops should be taken into the

Continental army, when he would be deprived of chief command.

Henry never forgot the treatment accorded him, nor did his

friends. When he resigned his commission in March, 1776, ready

tongues insinuated that the envy of the Committee had sought to

undermine his reputation and force him to the step. Supporters

of the government hastened to clear the Committee from blame.

The factional contest reappeared later in the contest over the

election of the President of the Virginia Convention,

and the question was discussed at large in the pages of the

Virginia Gazette.

Little judicial duty

fell to the Committee. As has been seen the first trial of

suspects rested with the judges appointed from the county

committees and commissioned by the Committee of Safety and cases

of appeal were only rarely brought before the latter.

The greater part of the

counties were well affected to the American cause but Princess

Anne and Norfolk contained many Tories who lent aid to Lord

Dunmore and gave intelligence of the plans of the Americans.

These districts were sometimes ravaged by parties from the

British fleet in search of provisions and the Committee of

Safety, at the suggestion of General Lee, determined upon the

extraordinary measure of removing the population of the two

counties into the interior to keep the friendly inhabitants from

harm, and to prevent the Tories from communicating with the

fleet. An order to this effect was issued April 10, 1776. All

inhabitants, whether friendly or hostile, that resided between

the shore and the American posts, were directed to remove at

once to the interior. To compel them to go, their live stock and

slaves were to be seized by the army and redelivered only when

they had complied with the order. All those in any part of the

two counties who had previously joined the British side or taken

oath to support it were to move at least thirty miles away from

the shore, and, to enforce submission, the slaves of all

suspected of belonging to this class were to be taken and to be

returned only at the order of the Committee, when the owners

were settled in some secure place. Three men were appointed to

superintend the matter and $1000 was to be advanced to them to

pay the expenses. All who were willing to provide dwellings for

the emigrants were requested to give notice in the Virginia

Gazette.

It is difficult to

justify a proceeding so arbitrary and so productive of needless

suffering. Its apologists have claimed that, though harsh, it

was rendered necessary by the danger of the time. This does not

seem probable, for Lord Dunmore had not shown himself able to

gain any ground in Virginia or to deal the Americans any

effective blow. The Committee may have feared the approach of

Howe’s fleet and army, but there was no certainty of their

coming. No serious danger threatened and it seems an

absurdity, in spite of the grave assertions of the Committee, to

depopulate the counties to protect them from marauding

expeditions and to prevent the Tories from furnishing the fleet

with supplies.

It was reasonably

certain that in leaving and losing their houses and land and

their business, in subjecting their live stock and slaves to the

uncertainty they must encounter before they were recovered and

in removing to a strange part of the Colony the inhabitants

would suffer more loss, discomfort and distress than it was

possible to receive from the enemy’s guns. As for the Tories it

would seem far less trouble to keep so vigilant a guard that

communication with the ships would be impossible than to attempt

the task of transporting them all into the interior. It is a

striking illustration of the despotic character of the

revolutionary governments and of the folly into which their

excessive fear of the British arms and their inexperience in

government led them.

Steps were soon taken to

enforce the order and Colonel Woodford was directed to take

general charge of the removal, and to deal with the people as

humanely as possible. Woodford complied and set about his task.

This high handed interference with persons and property aroused

inevitable opposition and a petition was sent to the Committee

from Princess Anne County setting forth the distress that would

ensue if the order was fully executed. It was therefore

reconsidered and modified to some extent. Six men were appointed

to find out those in the two counties who had taken active part

in behalf of the American cause, those who had remained quietly

neutral, and those who had appeared in opposition. The

commanding officer at Suffolk or vicinity was to allow the

friends and neutrals to remain unmolested, but to send into the

interior all live stock not necessary for their subsistence.

Those who had committed themselves against the cause were still

forced to remove with their families and effects.

The Convention met early

in May and the conditions were altered again. Besides the

Tories, the friendly inhabitants within certain sections were

ordered to leave because of the particular danger of their

situation. The rest were free to remain, unless the commander of

the neighboring troops, on urgent necessity, saw fit to remove

them. The expenses of the American sympathizers were to be paid

by the public, those of the disaffected from the sale of their

estates.

It was found, however,

that the people of the two counties were in distress for want of

food, and on May 16, a resolution was passed by the Convention

permitting the men of the Whig party to remain and care for

their crops, but obliging the removal of their families, slaves

and live stock. There was little probability of this order being

carried out. It took from the farmers the important service of

their cattle and slaves. It involved the separation of families

and placed the support of the women and children on the

government. Having conceded so much, it is not surprising to

find the convention a fortnight later rescinding the order for

removal entirely, as far as it related to friends.

The Tories were still compelled to leave.

In the absence of

evidence to the contrary it is reasonable to assume that the

orders against the Whigs may not have been rigidly enforced, and

that they may have suffered comparatively little. They were few

in number and the frequent issue of directions concerning them,

show that some at least must have remained in their homes

throughout. Between April 10 and May 3, the officers probably

waited to know the result of the petition. From May 3 to May 11,

when the first order of the Convention was passed the Whigs were

under the protection given by the Council. There remained then

only the time from the eleventh to the twenty-eighth when the

order was repealed, when they were in any considerable danger,

and during that period influence was probably busy to secure

delay, mitigation and at length the total repeal of the

obnoxious measure.

The Tories probably

suffered considerably. Lee writes from Suffolk, on April 23,

that he is busy clearing the country of them and an overseer of

the poor, in the county of Norfolk, speaks of the removal of a

great many of the inhabitants with their families and goods.

The confiscation of their estates made their departure

profitable to the government and it was therefore not likely to

be stopped.

The sufferings of the Tories

darken the pages of our revolutionary history. Men dreaded the

power of their numbers, their wealth and their influence, and

fear was quick to devise harsh measures. However successful its

work along other lines, the Virginia committee, in ordering the

removal of the Tories from Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties,

must stand condemned both for want of judgment and of humanity.

Military Career

Little is known of

Nicholas’ military career other than a brief note by Thomas

Jefferson dated August 18, 1813:

"Nicholas

Lewis, the second of his father's brothers, commanded a regiment

of militia in the successful expedition of 1776 against the

Cherokee Indians; who, seduced by the agents of the British

government to take up the hatchet against us, had committed

great havoc on our southern frontier, by murdering and scalping

helpless women and children, according to their cruel and

cowardly principles of warfare. The chastisement they then

received closed the history of their wars, and prepared them for

receiving the elements of civilization, which, zealously

inculcated by the present government of the United States, have

rendered them an industrious, peaceable, and happy people. This

member of the family of Lewises, whose bravery was so

successfully proved on this occasion, was endeared to all who

knew him by his inflexible probity, courteous disposition,

benevolent heart, and engaging modesty and manners. He was the

umpire of all the private differences of his country-selected

always by both parties. He was also the guardian of Meriwether

Lewis,...who had lost his father at an early age."

At the beginning of the

Revolution the Cherokee received a delegation from the Indians

north of the Ohio (Shawnee, Iroquois, Ottawa) to join them in a

war against the white settlements over the Blue Ridge. The

British offered guns, ammunition and cash payments for scalps

and sent officers among the Cherokee. Most of the Cherokee

declined this invitation and declared neutrality. However, the

Chickamauga faction, led by Tsi'-yu-gunsi-ni (Dragging Canoe)

did join in this war. Nancy Ward, the "beloved woman" of the

Cherokee sent runners to the settlements in northeast Tennessee

and Virginia's Clinch River valley warning of this attack.

Forewarned, the settlers at Watauga and Eaton's Station forted

up and beat off the attacks of 250-700 warriors in July of 1776

(estimates widely vary on the number of Chickamauga). Many of

the women and children in the Carter's Valley and Watauga

settlement left and temporarily found refuge in the New River

settlements.

In retaliation, militia

companies from southwest Virginia, western North Carolina and

the settlements in Tennessee gathered together and attacked the

Cherokee. The 1500 Virginians were led by Colonel William

Christian, they left for Cherokee lands in October of 1776,

returning in December, and then attacking again in April of

1777. They destroyed homes, livestock and crops of over 30

villages, both hostile and neutral. Most of the Cherokee fled

the villages before the militia arrived and put up little

resistance. According to Cherokee legend the inhabitants that

remained were slaughtered regardless of age and sex. On the

other hand, according to the reports of the militia officers and

later pension applications there were few killed on either side

and there is no mention that I have found of killing women and

children. Those women and children they found [and did not kill]

were according to official Virginia documents made prisoner and

Nancy Ward was brought back to Virginia (but was not considered

a prisoner according to official documents). However, there were

also attacks made on the Cherokee by the state militias of North

and South Carolina and Georgia and there are indications that

these men behaved in a less restrained fashion (e.g. 20 years

later in western Georgia Cherokee children still fled at the

sight of a white man). The Cherokee "made peace" (most had never

been at war).A peace

treaty was signed with the Carolinas and Georgia at DeWitt's

Corner on 20 May 1777 and with Virginia on 20 July 1777 at the

Long Island of the Holston. With the peace was a cession by the

Cherokee of over 5,000,000 acres of land.

Death

Col.Nicholas

Lewis died December 8, 1808 at 74 years of age. He is buried on

his property in a cemetery on a hilltop overlooking the river.

MaryWalker died February 9, 1824 at 81 years of age

Dr.

Thomas Walker

Thomas Walker

was born was born in Rye Field, King & Queens County,

Virginia January 15, 1715 the son of Maj. Thomas Walker and

Susannah Peachy. The Walkers of Virginia came from

Staffordshire, England about 1650 at an early period in the

history of the colony of Virginia. Major Walker was a member of

the Colonial Assembly 1662, being at that time a Representative

from the County of Gloucester. This gentleman, in 1663, claimed

that he planted 70,000 mulberry trees and therefore requested

bonuses for silk culture. In 1667 following the report of a

committee of the House of Burgess sent to count his trees, he

was awarded 20,000 pounds of tobacco for his efforts.

The

Explorer

Dr. Thomas Walker was one of the great explorers of southwestern

Virginia, crossing Cumberland Gap (what he called Cave Gap) on

April 17, 1750 and "discovering" Kentucky. He was not the first

person to cross the gap - Native Americans had lived in the area

for perhaps 10,000 years. As Walker recorded in his journal, he

was not even the first European to cross it and mark the

passage:

“April 13th.

We went four miles to large Creek which we called Cedar Creek

being a Branch of Bear-Grass, and from thence Six miles to Cave

Gap, the land being Levil. On the North side of the Gap is a

large Spring, which falls very fast, and just above the Spring

is a small Entrance to a Large Cave, which the spring runs

through, and there is a constant Stream of Cool air issueing

out. The Spring is sufficient to turn a Mill. Just at the Foot

of the Hill is a Laurel Thicket and the spring Water runs

through it. On the South side is a Plain Indian Road. on the top

of the Ridge are Laurel Trees marked with Crosses, others Blazed

and several Figures on them. As I went down the other Side, I

soon came to some Laurel in the head of the Branch. A Beech

stands on the left hand, on which I cut my name.”

Family

After studying medicine with his

sister's husband Dr. George Gilmer, Thomas set up practice in

Fredericksburg and became a noted physician. He also ran a

general store and engaged in an import and export trade.

In 1741 married Mildred

Thornton Meriwether. She was born March 19, 1721in Louisa,

Virginia, the daughter of Col. Francis Thornton and Alice

Savage. Mildredxe "Meriwether:Mildred Thornton (1721-1778)"

married twice, first to Nicholas Meriwether III and then to Dr.

Thomas Walkerxe "Walker:Dr. Thomas (1715-1794)". Thomas Walker

and Mildred Meriwether had 12 children:

-

MILDRED WALKER, b. Castle Hill, Albemarle

County, VA.

-

MARY (Capt. Molly) WALKER,xe "Walker:Mary

(Capt. Molly) (1742-1824)" b. 1742.

-

COL. JOHN WALKER, b. Castle Hill,

Albemarle County, VA 1743, d. 1809 in Madison's Mill, Orange

County, VA

-

SUSAN WALKER, b. Castle Hill, Albemarle

County, VA 1746, d. Albemarle County, VA.

-

DR. THOMAS WALKER JR., b. Castle Hill,

Albemarle County VA 1748.

-

LUCY WALKER, b. Castle Hill, Albemarle

County, VA 1751.

-

ELIZABETH WALKER, b. Castle Hill,

Albemarle County, VA 1753.

-

SARAH WALKER, b. Castle Hill, Albemarle

County, VA 1758.

-

MARTHA WALKER, b. Castle Hill, Albemarle

County, VA 1760.

-

REUBEN WALKER, b. Castle Hill, Albemarle

County, VA 1762, d. 1765.

-

HON. FRANCIS WALKER, b. Castle Hill,

Albemarle County, VA 1764, d. 1806.

-

PEACHY WALKER, b. Castle

Hill, Albemarle County VA 1767.

Castle Hill

By marriage,

Thomas Walker acquired 11,000 acre estate known as Castle Hill.

|

The

original wooden structure was completed in 1765 and

faced the mountains to the northwest. Walker would

reside at Castle Hill until his death on November 9,

1794. Walker's son Francis would succeed to the Castle

Hill estate, after his father made him power of attorney

until his death in 1806. Judith Rives (1802-1880),

granddaughter of Thomas Walker, who married the Hon.

William C. Rives a senator, lived at Castle Hill for the

duration of her life. Today the home has been added on

to and remodeled many times, but the original structure

still

stands. Walker would continue

to acquire land throughout his life. For example in

1772, Lord Dunmore gave Walker another land grant of 226

acres within Albemarle County. |

Castle Hill also

played host for a short time to the British enemy Banastre

Tarleton on June 4, 1781 during the midst of the American

Revolution. There Tarleton made a short stay, but was delayed by

the insisting of Mildred Walker. This delay gave the young Jack

Jouett of Louisa County enough time to reach Charlottesville and

send a messenger to warn Thomas Jefferson and her legislators

staying at Monticello, who escaped just in time safely into

Staunton, Va. in the Shenandoah Valley. Tarleton's short visit

at Castle Hill proved to be a critical moment in the Revolution

by saving members of the General Assembly and giving the

citizens of Charlottesville time to prepare or flee.

Castle Hill also

played host to many Native American chieftains who would stop at

Walker's home on their journeys to Williamsburg. Walker used

these opportunities to learn about practices and psychology of

different tribes, and to gain information about the consistency

of wildlife and woodlore in the unknown west.

1749-1777

In 1749 Thomas became chief agent of Loyal

Land Company, which had received a grant of 800,000 acres from

the council of Virginia and in the following years he led an

expedition to explore lands of this grant. He kept a journal of

the trip which was the first record of a white man in what was

to become Kentucky. In 1775, during the French and Indian Wars,

he became Commissary to Virginia troops under George Washington

and was later charged with fraud, but acquitted. A copy of his

journal can be viewed at:

http://www.tngenweb.org/tnland/squabble/walker.html

Dr. Thomas Walker served on the

Committee of Safety in Virginia. In 1777 he was appointed with

his son Col. John Walker to visit Indians in Pittsburgh, Pa. for

the purpose of gaining their friendship for the Americans.

The Walker Line

In 1776 the Virginia House of

Delegates defined the northern boundary of the Kentucky District

as the low-water mark at the mouth of the Big Sandy, on the

northern shore of the Ohio River. This boundary followed the Big

Sandy River from that point to the junction of the Tug Fork, and

from there up to the Laurel Ridge of the Cumberland Mountain to

the point where it crossed the Virginia-North Carolina line

(known as "seven pines and two black oaks). When Virginia agreed

to separate Kentucky in the Compact of 1789, that description

was accepted.

In 1779-80, The

Virginia-North Carolina dividing line was extended westward to

the first crossing of the Cumberland River. From this point west

to the Mississippi, Thomas Walker surveyed the line for

Virginia. This took him through dense forests, over rugged

mountains - a most difficult task. According to R. S. Cottrill,

in an article dated 1921, this line almost immediately caused a

tremendous amount of dispute for many years between Kentucky and

Tennessee. When Kentucky became a state in 1792, it immediately

began to "find fault" with the line as drawn by Thomas Walker in

1779.

Before 1779 the line

between Virginia and North Carolina was run at 36 30' degrees

toward the Cumberland Gap. This is commonly known as the 36-30

line. In 1779, Dr Thomas Walker and Daniel Smith were chosen by

Virginia to extend the line to the Tennessee River. Their party

included Col Richard Henderson and William B Smith of North

Carolina. The men ran into tremendous obstacles and disputes

almost immediately when they decided to run two separate lines

to the Cumberland Gap. Henderson refused to proceed and the

Walker party continued and by the time they reached the

Cumberland River, they found themselves several miles too far

north. The Walker party then continued to run their line only to

the Tennessee River but on to the Mississippi River.

In 1799, in an effort to solve

the boundary problem, the Virginia House of Delegates created a

commission comprised of John Coburn, Robert Johnson and Buckner

Thruston. They met with the Virginia delegation of Archibald

Stewart, Gen Joseph Martin and Creed Taylor. They began their

survey at the forks of the Big Sandy and followed east along the

Tug Fork to the Breaks of Sandy. They then went northeast from

the Walker line at the spot known as the seven pines and two

black oaks, went up the watershed of the Cumberland Mountain to

the crossing of the Russell Fork of the Levisa Fork - and thence

along a magnetic line 45 degrees east longitude to the crossing

of the Tug Fork.

That same year, 1799, a joint commission settled Kentucky's

eastern and northeastern boundaries, the rest of the boundaries

were not handled. Westward from the ridge top of the Cumberland

Mountain, the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina

(later, 1796, Tennessee) remained questionable because of the

Walker Survey of 1779.

In 1801, the Kentucky

Legislature appointed commissioners to ascertain and mark her

southern boundary. This did not occur for some reason until 1812

- in fact five times the Legislature took up this problem. Over

ten times in a ten-year period (1820-1830), the Kentucky

legislature tackled the problem, still feeling that Kentucky had

been cheated out of its own land - and finally commissioners

were appointed to represent Kentucky and Tennessee to settle the

problem.

Crittenden represented

Tennessee and Rowan represented Kentucky. Felix Grundy and W J

Brown were to assist in looking out for the interests of

Tennessee. They met in January of 1820 in Frankfort and decided

to communicate by writing. The Tennessee commissioners stood by

the old Walker line and refused to consider any other line. They

felt they had the right to it as their citizens had settled in

this area and they were Tennesseans and would not become

Kentuckians! Crittenden urged Rowan to give up the idea and let

the line stand, but John Rowan was determined and stubborn and

refused to take any line other than what is known as the 36-30

line along the entire boundary. Thus, nothing was accomplished.

In 1821, the

commissioners from both states were back to work and started

running the line again as if there had been no problems in the

past. Kentucky appointed William Steele and Munsey to represent

them and Absalom Looney represented Tennessee. They ran the line

again, they thought, on the 36-30 line and marked it extremely

carefully to the Cumberland River. But it was found later that

they had really started at 36-34 and ended at 36-37 but was a

little more accurate that the original Thomas Walker drawn line.

On the first of May 1821 they began on the Cumberland Mountain

and on July 2nd, they concluded it at the crossing of the

Cumberland River and joined the original Walker line - just

above John Kerr's house. The Tennessee representatives approved

the survey but the line westward was uncertain until a 1859

survey by Austin P Cox and Benjamin Pebbles.

That did not settle the

dispute. By 1825 the Kentucky Legislature is again questioning

the boundary and so the state hired a mathematician to relocate

the line. Thomas Matthews was appointed to handle this task and

was paid over $2,000 for his services. Beginning with his

findings, the boundary question shifted from the east to the

west of the Cumberland River. It seems that when Walker ran the

original line, the western part of Kentucky still belonged to

the Chickasaw Indians and Walker stopped at the Tennessee River.

Kentucky had later purchased this land and its boundaries had to

be fixed. More disputes arose between Tennessee and Kentucky

over the next few years and many times, the representatives from

each state were deadlocked. The land around Reelfoot Hills and

the southern boundary of Trigg County, KY was the most difficult

to establish and it often seemed a total impossibility to

determine the line.

With the battle still raging,

in 1845 the Kentucky Legislature again named commissioners to

run the boundary. Wilson and Duncan were named along with a

representative from Tennessee and they attempted to mark the

boundary of Christian, Trigg and Fulton Counties. The noted

Joseph Rogers Underwood of Barren and Warren County was named to

this commission but resigned.

The difficulties continued madly into the

1850's. In 1858 the Kentucky Legislature authorized the Governor

of Kentucky to again name commissioners to once and for all

determine the boundary lines. Austin P Cox and Charles M Briggs

met with two Tennessee commissioners (Peoples and Watkins) the

next year and made a successful attempt to find and locate the

entire line. They ran a resurvey east of the Cumberland and

corrected the former lines west of that river.

In 1859, the Cox-Pebbles

team traveled a 320 mile course between January 9th and October

20th. It covered the same terrain that Walker's party had

traveled from New Madrid Bend to the Cumberland Gap. They

erected 3 foot high stone slabs every five miles to mark the

line - beginning at Compromise on the Mississippi River and

ending at the spot where the old Wilderness Road passed through

the Cumberland Gap.

In today's age of technology,

satellite mapping and precision surveying, it is hard to realize

what difficulties all these men through the years encountered in

trying to map out and determine the boundary lines. But, you

might ask - what was gained by all these many years of

struggling, fighting and legislature sessions? Kentucky gained

the 36-30 line for its boundary only west of the Tennessee River

and east of that river, the line is basically what it was as

marked by Walker in 1799. It has been rumored down through the

pages of time, that there was a lot of "wheeling and dealing"

under the surface also. Farmers who possibly bribed the

surveyors by a little moonshine to let their land lie in

Kentucky or Tennessee (Moonshine was legal in Tennessee during

many of these years and illegal in Kentucky).

Death

|

Dr. Thomas Walker

died

November 9, 1794 at Castle Hill, Albemarle County

Virginia, at 79 years of age. Mildred died November 16,

1778 at Castle Hill, Albemarle County, VA, at 57 years

of age. They are buried on the estate. The cemetery is

situated near the foot of the mountain in the woods

surrounded by a brick wall. |

Lt. Hudson Martin

Hudson Martin

was born in Saline

County, Missouri July 3, 1752. He enlisted as an ensign under

Capt. James Alexander on March 11, 1776 and was promoted to

Lieutenant on March 26, 1776. Lt. Martin was wagon master at

Lancaster, Pa. in 1778 but resigned in April of the same year.

He was appointed by Gov. Patrick Henry, Paymaster to the

Regiment of Guards, commanded by Col. Francis Taylor from

January 1779 to August 1781, at which time the regiment was

disbanded. They were stationed at Albemarle to guard the

prisoners captured October 1777, at the surrender of Gen.

Burgoyne, at Saratoga. According to his pension papers, Hudson

Martin was drafted in Fluvanna County, as a militiaman in 1781

when he took the place of his brother William.

Family

Hudson Martin married Jane Walker

Lewis in Saline County, Missouri, December 2, 1778. Jane was

the daughter of Col. Nicholas Lewis and Mary Walker mentioned

earlier. The family settled southwest of Charlottesville,

Virginia in the counties of Albemarle and Nelson, near Rockfish

Gap & River. They had nine children:

-

NICHOLAS LEWIS MARTIN, b. 1779, d. 1787.

-

HUDSON MARTIN II, b. 1781.

-

JOHN MASSIE MARTIN, b. 1783, d. 1851.

-

MARY (Molley) WALKER MARTIN, b. 1787.

-

JANE LEWIS MARTIN, b. 1790.

-

NICHOLAS LEWIS (2nd) MARTIN, b. 1791.

-

HENRY BUCK MARTIN, b. 1794, d. 1828.

-

GEORGE WASHINGTON MARTIN, b. 1796.

-

MILDRED HORMSLEY MARTIN, b.

1801.

Death

Hudson Martin

died November 28, 1830 in Fayette County, Maryland, at 78 years

of age. His will was executed June 23, 1828, and is on record

in Nelson Co. Va., and a copy of it is on file in the Pension

Office at Washington, D.C. Judging from the bequests of real

estate, slaves and money to the several members of his family,

he was a man of considerable wealth and influence in the county

in which he resided. The executors to his estate gave bonds to

the amount of 20,000 pounds. Jane Walker Lewis died August 15,

1838 in Albermarle County, Virginia, at 81 years of age.

Pvt. William T. Duggins

William was born in Dublin, Ireland

October 31, 1751. William was an only child. After his

father’s (William) death he came with his mother, Alice, to

Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania Co, Virginia in 1763. She

afterwards married Robert Wilkinson, by whom she had three

children, and then died in Fredericksburg. William was

apprenticed to a silversmith in Louisa County, Virginia.

Service

He enlisted

January 20, 1777 in Capt. William Vanse's Co. 12th Va. Regiment

to serve during the Revolutionary War. He was transferred about

June 1778 to Col. James Woods' Co., 4th, 8th & 12th Va.

Regiments, and about October 1778 to Capt. William Vanse's Co.

8th. Va. Regiment, commanded by Col. James Woods. His name last

appears on the Co. muster roll for November 1779, dated at camp

near Morristown December 9, 1779 without special remark relative

to his service.

Family

William married Elizabeth Perkins

December 16, 1787, daughter of William Perkins, of a well-known

South Carolina family of that name. He was a member of the

Episcopal Church, and a devout Christian. Elizabeth was born in

South Carolina, in 1771. William and Elizabeth had 14 children:

-

POLLY DUGGINS, b. 1788, Louisa County

Virginia.

-

JANE DUGGINS, b. 1790, Louisa County

Virginia.

-

ROBERT DUGGINS, b. 1792, Louisa County

Virginia; d. bef. 1872, Virginia.

-

WILLIAM DUGGINS,JRxe "Duggins:William

(1794-dec.)", b. 1794, Louisa County, Virginia; d. Hanover

Co., Virginia.

-

JOHN D. DUGGINS, b. 1796, Louisa County,

Virginia; d. 1865, Saline County, Missouri.

-

GEORGE DUGGINS, b. 1798, Louisa County,

Virginia; d. aft. 1873.

-

POUNCY DUGGINS, b. 1800, Louisa County,

Virginia.

-

JEFFERSON DUGGINS, b. 1802, Louisa

County, Virginia; d. bef. 1873, Virginia.

-

WASHINGTON DUGGINS, b. 1804, Louisa

County, Virginia.

-

JAMES MADISON DUGGINS, b. 1806, Louisa

County, Virginia; d. 1865, Virginia.

-

LEWIS H. DUGGINS, b. 1808, Louisa County,

Virginia; d. 1875.

-

THOMAS CRUTCHFIELD DUGGINS, b. 1810,

Louisa County, Virginia; d. 1880 Marshall, Missouri.

-

FLEMING P. DUGGINS, b. 1812, Louisa

County, Virginia.

-

FRANKLIN A. DUGGINS, b. 1814, Louisa

County, Virginia.

Death

William T.

Duggins died June 23, 1827 in Louisa County, Virginia, at 75

years of age. Elizabeth Perkins died December 17, 1823 in Louisa

County, VA at 52 years of age.

|