|

Our Confederate Ancestor

PRINT Version

of this article

Link to

National Society of the

Sons of Confederate Veterans Back to

|

INTRODUCTION

The American

Civil War (1861–1865) was a war between the United States

Federal government (the "Union") and eleven Southern slave

states that declared their secession and formed the Confederate

States of America, led by President Jefferson Davis. The Union,

led by President Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party,

opposed the expansion of slavery and rejected any right of

secession. Fighting commenced on April 12, 1861, when

Confederate forces attacked a Federal military installation at

Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

During the first

year, the Union asserted control of the border states and

established a naval blockade as both sides raised large armies.

In 1862 the large, bloody battles began. In September 1862,

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation made the freeing of the

slaves a war goal, despite opposition from northern Copperheads

who tolerated secession and slavery.

Emancipation

ensured that Britain and France would not intervene to help the

Confederacy. In addition, the goal also allowed the Union to

recruit African-Americans for reinforcements, a resource that

the Confederacy did not dare exploit until it was too late. War

Democrats reluctantly accepted emancipation as part of total war

needed to save the Union. In the East, Robert Edward Lee rolled

up a series of Confederate victories over the Army of the

Potomac, but his best general, Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall"

Jackson, was killed at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May

1863. Lee's invasion of the North was repulsed at the Battle of

Gettysburg in Pennsylvania in July 1863; he barely managed to

escape back to Virginia. In the West, the Union Navy captured

the port of New Orleans in 1862, and Ulysses S. Grant seized

control of the Mississippi River by capturing Vicksburg,

Mississippi in July 1863, thus splitting the Confederacy.

By 1864, long-term

Union advantages in geography, manpower, industry, finance,

political organization and transportation were overwhelming the

Confederacy. Grant fought a number of bloody battles with Lee in

Virginia in the summer of 1864. Lee won most of the battles in a

tactical sense but on the whole lost strategically, as he could

not replace his casualties and was forced to retreat into

trenches around his capital, Richmond, Virginia. Meanwhile,

William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta, Georgia. Sherman's

March to the Sea destroyed a hundred-mile-wide swath of Georgia.

In 1865, the Confederacy collapsed after Lee surrendered to

Grant at Appomattox Court House and the slaves were freed.

The full

restoration of the Union was the work of a highly contentious

postwar era known as Reconstruction. The war produced about

970,000 casualties (3% of the population), including

approximately 620,000 soldier deaths—two-thirds by disease. The

causes of the war, the reasons for its outcome, and even the

name of the war itself are subjects of lingering controversy

even today. The main results of the war were the restoration and

strengthening of the Union, and the end of slavery in the United

States.

This is the biography of our

Confederate Ancestor, John William Duggins, Pvt, Company E, 5th

MO Cavalry, Gordon's Regiment, Company H Shelby's "Iron

Brigade.”

WILLIAM T. DUGGINS

immigrated to America from Dublin, Ireland with his mother Alice

in 1763 after the death of his father (William). They settled in

Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania County, Virginia. He was

apprenticed to a silversmith in Louisa County, Virginia.

He enlisted January 20,

1777 in Capt. William Vanse's Co. 12th Va. Regiment to serve

during the Revolutionary War. He was transferred about June

1778 to Col. James Woods' Co., 4th, 8th & 12th Va. Regiments,

and about October 1778 to Capt. William Vanse's Co. 8th. Va.

Regiment, commanded by Col. James Woods. His name last appears

on the Co. muster roll for November 1779, dated at camp near

Morristown December 9, 1779 without special remark relative to

his service.

William married

Elizabeth Perkins December 16, 1787, daughter of William

Perkins, of a well-known South Carolina family of that name. He

was a member of the Episcopal Church, and a devout Christian.

Elizabeth was born in South Carolina, in 1771. William and

Elizabeth had 14 children.

Children of WILLIAM T.

DUGGINS and ELIZABETH PERKINS are:

-

POLLY DUGGINS, b. 1788, Louisa County,

Virginia.

-

JANE DUGGINS, b. 1790, Louisa County,

Virginia.

-

ROBERT DUGGINS, b. 1792, Louisa County,

Virginia; d. bef. 1872, Virginia.

-

WILLIAM DUGGINS,JRxe "Duggins:William

(1794-dec.)", b. 1794, Louisa County, Virginia; d. Hanover

Co., Virginia.

-

JOHN D. DUGGINS, b. 1796, Louisa

County, Virginia.

-

GEORGE DUGGINS, b. 1798, Louisa County,

Virginia; d. aft. 1873.

-

POUNCY DUGGINS, b. 1800, Louisa County,

Virginia.

-

JEFFERSON DUGGINS, b. 1802, Louisa

County, Virginia; d. bef. 1873, Virginia.

-

WASHINGTON DUGGINS, b. 1804, Louisa

County, Virginia.

-

JAMES MADISON DUGGINS, b. 1806, Louisa

County, Virginia; d. 1865, Virginia.

-

LEWIS H. DUGGINS, b. 1808, Louisa County,

Virginia; d. 1875.

-

THOMAS CRUTCHFIELD DUGGINS, b. 1810,

Louisa County, Virginia; d. 1880 Marshall, Missouri.

-

FLEMING P. DUGGINS, b. 1812, Louisa

County, Virginia.

-

FRANKLIN A. DUGGINS, b. 1814, Louisa

County, Virginia.

William died June 23, 1827 in

Louisa County, Virginia, at 75 years of age. Elizabeth died

December 17, 1823 in Louisa County, VA at 52 years of age.

JOHN D. DUGGINS was born in Louisa

County, Virginia May 1, 1796. He married Frances Elizabeth

Dickinson January 20, 1823. The Bondsman for the wedding was

Lt. Hudson Martin (see Our American Revolution Ancestors).

Francis was born in Fulton, Callaway Co. Missouri January 11,

1808. She was the daughter of Thurston Dickinson and Mary

Martin.

|

John and

Frances moved from Virginia and settled on the “Moss

White Farm” (three miles west of Marshall) Saline

County, Missouri in 1834. Together they established the

first boarding school in the county which they

maintained for ten years. John first built a house,

part log and part frame. He hauled lumber for the

flooring of his house from Chamber's mill, over the Big

Bottom. As the number of pupils increased, so did the

size of the Duggins mansion.

John and Frances had two children:

1.

ELIZABETH MARSHALL DUGGINS, b. 1828, Saline County,

Missouri;

d. 1904.

2. JOHN WILLIAM

DUGGINS, b. 1839, Saline County, Missouri.

In 1850, John and

Frances moved to Cambridge, Missouri. |

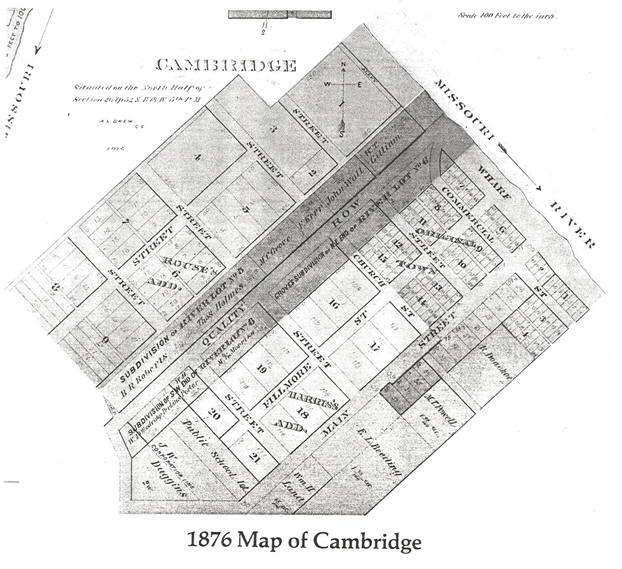

Cambridge, Missouri

After a change in the channel

direction of the Missouri River destroyed the town of Jefferson,

Missouri in 1845, a settlement developed less than a mile down

river which was to become known as Cambridge.

The town adopted its

name from the township and one supposition is that the name

Cambridge came from Cambridge, Mass., and the fact that the

first county clerk, Benjamin Chambers, son of a revolutionary

war general who won fame at the battle of Cambridge, was

probably the reason the town was given the name. Frederick A.

Brightwell, the first businessman and the first postmaster of

Cambridge is credited with giving the town the name although

there is no historical validation.

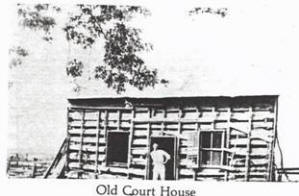

Although Cambridge was first occupied in 1845, it was not until

1848 that the town itself was regularly laid off. By 1876 the

population had grown to around 450 people. Among other

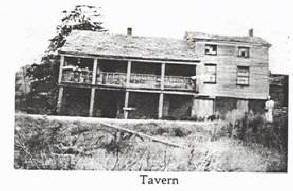

businesses and at various times there were four general stores

dealing in dry goods, hardware and groceries, a harness shop,

two drug stores, one or two tobacco factories, hemp bailing

machines, a tin and hardware store, steam mill, wagon maker’s

shop, blacksmith shop, and a grog shop that was heavily

patronized on Saturdays. The town well with its oaken bucket

was at the south end of Main Street.

|

The town had

a levee, or wharf, as it was called where the steamboats

landed. The wharf was graded to an even slope from the

top of the river bank to the water’s edge and paved with

limestone. It was during these years and prior that the

town enjoyed its greatest days of prosperity, when busy

boats plied their trade up and down the Missouri River

carrying cargoes of necessities and luxuries and

sometimes entertainment from the outside world inland,

and returning with cargoes of just as much necessity

such as pelts, hemp and tobacco to the outside world.

There was a school and a Methodist

church. The church had originally been organized in

1837 in a school house in Jefferson. As Cambridge

itself began to build up, the place of the church

meeting was changed to Cambridge and in 1853 a house of

worship was erected. Years later the church merged with

the Gilliam Methodist church.

One parishioner

recalled the hymns were started by a leader who, by the

trial and test manner using a tuning fork, established

the right pitch for singing. The women sat on the west

side of the church with the men on the east side. The

“amen Corner” was in the northwest part of the church

and usually occupied by the older members. A gallery

for the colored members was in the rear of the church.

The church was

later occupied by Wisconsin troops at the close of the

Civil War and a stockade built around the church.

The first mill

in Saline County was built in 1817 about one mile below

Cambridge. It was operated by horse power and only

ground corn and wheat. During the heydays in Cambridge

a Mr. Donahoe operated a mill in Cambridge that was

equipped with a single cylinder steam engine. This

ground the grain between two old-time millstones. The

flour was sifted through cloths that held the chaff and

the bran.

Wyatt Earp,

noted frontiersman and gun fighter, once lived near this

community. Nicholas P. Earp and his family came to the

county around 1870 and lived on a farm two and one-half

miles east of Gilliam. Nicholas had four sons, Virgil,

Morgan, Wyatt, and Warren and one Daughter, Adelia.

They lived there until 1877 when Nicholas and his wife

and youngest son, Warren, moved by covered wagon to

California. The three older Earp brothers moved to

Dodge City some years before.

With the building of

the Chicago and Alton Railroad, or rather by its

location away from Cambridge, and the building of the

towns of Slater and Gilliam, Cambridge was abandoned. |

John D. Duggins died

July 22, 1865 in Fulton, Missouri, at 69 years of age. His

body was interred in Cambridge. Francis Elizabeth Dickinson

died May 27, 1880 in Fulton at 72 years of age. Her body

was also interred in Cambridge.

|

John D. Duggins

1796-1865

Good Hope Cemetery

Cambridge, MO

|

Frances Elizabeth

Dickinson

1807-1880

Good Hope Cemetery

Cambridge, MO |

JOHN WILLIAM DUGGINS was

born in Cambridge, Saline County, Missouri November 16, 1839.

John assisted his father in management of his farm of 1,200

acres. He followed farming all his life, except four during

which he served as township constable and three years in

Confederate service, under the command of General Shelby.

The Fifth Missouri

Cavalry was organized in the spring of 1862. The regiment was

known frequently by its nickname, or local designation, of the

Jackson County Regiment or the Jackson County Cavalry. A great

many members of the regiment were recruited in that county and

in nearby counties in western Missouri.

Like most Civil War

units the Fifth Missouri Cavalry was often known by alternate

designations derived from the name of its commanding officer.

Unofficial names for the Fifth Missouri included: Joseph O.

Shelby's Cavalry Y.M. Blackwell's Cavalry B. Frank Gordon's

Cavalry George R. Kirtley's Cavalry George P. Gordon's Cavalry

James Garrett's Cavalry George S. Rathburn's Cavalry D. R.

Stallard's Cavalry William H. Farrell's Cavalry.

Joseph Orville Shelby

Joseph Orville "JO"

Shelby (December 12, 1830 – February 13, 1897) was born in

Lexington, Kentucky, to one of the state's wealthiest and most

influential families. He lost his father at age 5, and was

raised by a stepfather. Shelby attended Transylvania University

and was a rope manufacturer until 1852. He then moved to

Waverly, Missouri, where he engaged in steam boating on the

Missouri River and in running a hemp plantation. He was one of

the largest slaveholders in the state. During the "Bleeding

Kansas" struggle, he led a company on the pro-slavery side.

In 1861, Shelby formed a

cavalry company and was elected its captain, leading it into

battle at Wilson's Creek. Promoted to colonel, he commanded a

brigade at Prairie Grove. Shelby led his "Iron Brigade" of

Missouri volunteers on what was to be the longest cavalry raid

of the war at that time, Shelby's Great Raid.

Between September 22 and

November 3, 1863, Shelby's brigade travelled 1,500 miles through

Missouri, inflicting over 1,000 casualties on Union forces, and

capturing or destroying an estimated $2 million worth of Federal

supplies and property. He was promoted to brigadier general on

December 15, 1863, at the successful conclusion of his raid.

In 1864, Union General

Steele's failure in the Camden Expedition (March 23–May 2,

1864,) can in no small part be laid to Shelby's brilliant and

determined harassment, though in concert with other Confederate

forces. Ultimately that Federal force was forced back to Little

Rock upon the final destruction or capture of its supply trains

at Mark's Mill. Reassigned to the Clarendon, Arkansas area,

Shelby accomplished the rare feat of capturing a Union tinclad

USS Queen City, which was immediately destroyed to avoid

recapture. As summer was ending Shelby then commanded a division

during Sterling Price's Missouri raid. He distinguished himself

at the battles of Little Blue River and Westport, and captured

many Union held towns, including Potosi, Boonville, Waverly,

Stockton, Lexington, and California, Missouri.

Shelby's adjutant was John

Newman Edwards, who later as editor of the Kansas City Times

was to almost single handedly create the anti-hero legend of

Jesse James.

After Robert E. Lee's army

surrendered in Virginia, General Edmund Kirby Smith appointed

Shelby a major general on May 10, 1865. However, the promotion

was never formally submitted, due to the collapse of the

Confederate government.

The Fifth Missouri

Cavalry served the Trans-Mississippi region throughout its

career. It served both in the Trans-Mississippi Department and

in the Army of Trans-Mississippi.

The Fifth Missouri

Cavalry was stationed near Shreveport, Louisiana when it

received the news of the surrender of the Confederate forces

east of the Mississippi River. The regiment was disbanded in

mid-May, 1865. General Shelby, along with approximately 1,000

of his remaining troops rode south into Mexico. For their

determination not to surrender, they were immortalized as "the

undefeated". A later verse appended to the angry post-war

Confederate anthem, "The Unreconstructed Rebel" commemorates the

defiance of Shelby and his men:

"I won't be

reconstructed, I'm better now than then. And for a

Carpetbagger I do not give a damn. So it's forward to the

frontier, soon as I can go. I'll fix me up a weapon and

start for Mexico."

Their plan was to offer

their services to Emperor Maximilian as a 'foreign legion.'

Maximilian declined to accept the ex-Confederates into his armed

forces, but he did grant them land for an American colony in

Mexico near Veracruz. The grant would be revoked two years later

following the collapse of the empire and Maximilan's execution.

Reportedly, Shelby sank his battle flag in the Rio Grande near

present-day Eagle Pass (TX) on the way to Mexico rather than

risk the flag falling into the hands of the Federals. The event

is depicted in a painting displayed at the Eagle Pass City Hall.

The memory of Shelby and his men as "The Undefeated" is used as

a distant basis for the 1969 John Wayne-Rock Hudson film by the

same name.

Shelby returned to Missouri

in 1867 and resumed farming. He was appointed the U.S. Marshal

for the Western District of Missouri in 1893, was a critical

witness for the defense of Frank James at his trial, and

retained the position until his death in 1897. He died in

Adrian, Missouri, and is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, Kansas

City.

Slayback's Missouri

Cavalry Battalion was organized in northern Arkansas during the

late spring of 1864. Most members of the battalion appear to

have been recruited in Wright, Texas, Douglas, Christian,

Lawrence, Dade, Barton, Jasper, Newton, and McDonald Counties.

Some members had served in State guard organizations early in

the Warand in a number of regular and irregular organizations

subsequently. At various times during the battalion’s short

career its members of companies grew from four to seven.

The battalion was also

known by the names of: Alonzo W. Slayback's Cavalry Thomas J.

Stirman's Cavalry Albert R. Randall's Cavalry. The battalion

served its entire career in the Trans-Mississippi Department.

Two specific higher command assignments were: July 31, 1864

Unbrigaded, First Missouri Cavalry Division, Cavalry, Army of

Trans-Mississippi.

John W. Duggins enlisted in

Company E, 5th Missouri Cavalry in Saline County,

Missouri on August 18, 1862 by Col. J.O. Shelby.

Co. E 5th Missouri

Cavalry

Company Muster Roll

August 18th – December 31st 1862

John W. Duggins, Private, Co. E Gordon’s Regiment, Missouri

Cavalry

Company Muster Roll

August 18th – December 31st 1862

Battle of Pilot Grove

Private Duggins fought in The Battle of Pilot Grove

on 7 December 1862. It resulted in a tactical stalemate but

essentially secured northwest Arkansas for the Union.

In late 1862 Confederate

forces had withdrawn from southwest Missouri and were wintering

in the wheat-rich and milder climate of northwest Arkansas. Many

of the regiments had been transferred to Tennessee, after the

defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March, to bolster the Army

of Tennessee.

Following Pea Ridge, the

victorious Union General Samuel Curtis pressed his invasion of

northern Arkansas with the aim of occupying the capital city of

Little Rock. Curtis's army reached the approaches to the

capital, but decided to turn away after a minor yet

psychologically important Confederate victory at the Battle of

Whitney's Lane near Searcy, Arkansas.

Curtis reestablished his supply

lines at Helena, Arkansas, on the Mississippi River and ordered

his subordinate, General John M. Schofield at Springfield,

Missouri, to drive Confederate forces out of southwestern

Missouri and invade northwestern Arkansas.

Schofield divided his Army of

the Frontier into two parts, one to remain near Springfield

commanded by General Francis J. Herron, and the other commanded

by General James G. Blunt to probe into northwest Arkansas.

Schofield soon fell ill and overall command passed to General

Blunt. As Blunt took command, the two wings of his army were

dangerously far apart.

Confederate General Thomas

C. Hindman was an aggressive commander who had just been

relieved of overall command of the Trans-Mississippi District.

Hindman had issued a series of unpopular, but effective,

military decrees which gave political opponents ammunition to

have him removed from overall command.

Hindman maintained a field

command of Arkansas troops and, becoming aware of the Union

Army's precarious tactical position, convinced his replacement

to allow him to mount an expedition into northwest Arkansas.

Hindman hoped to catch the Union army in its divided state,

destroy it in detail, and open the way for an invasion of

Missouri.

Hindman's force gathered at

Fort Smith, Arkansas, and sent out approximately 2,000 cavalry

under General John S. Marmaduke to harass Blunt's forces and

screen the main Confederate force.

Unexpectedly Blunt moved

forward with his 5,000 men and 30 artillery pieces to meet

Marmaduke. The two clashed in a nine-hour running battle known

as the Battle of Cane Hill on 28 November 1862. Marmaduke was

pushed back but Blunt found himself 35 miles deeper into

Arkansas and that much farther from the remainder of his army.

On 3 December Hindman

started moving his main body of 11,000 poorly equipped men and

22 cannon across the Boston Mountains toward Blunt's division.

Blunt, disturbed by his precarious position, telegraphed Herron

and ordered him to march immediately to his support from

Springfield. Blunt did not fall back towards Missouri but

instead set up defensive positions around Cane Hill to wait for

Herron.

Hindman's intention was for

Marmaduke's cavalry to strike Blunt from the south as a

diversion. Once Blunt was engaged, Hindman intended to hit him

on the flank from the east.

At the dawn of the 7th of

December Hindman began to doubt his initial plan to move on Cane

Hill and instead continued North on Cove Creek Road with

Marmaduke's men in the front. Why Hindman changed his mind is

not known, but it is believed, as all generals, that he began to

doubt his initial strategy. Little did Hindman realize though

that this move would prove useful and allow his cavalry to

strike an early deadly blow to the 7th Missouri and the 1st

Arkansas.

Meanwhile, Herron's

divisions had performed an amazing forced march to come to

Blunt's rescue and met Marmaduke's probing cavalry south of

Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Hindman's characteristically

aggressive nature seems to have failed him at this moment.

Afraid that Blunt would be able to attack his rear, and facing

Herron to the north, Hindman chose instead to set up a defensive

position atop a line of low hills near Prairie Grove, Arkansas.

The battle opened on the

morning of 7 December with Union General Herron crossing the

river and deploying his footsore troops on Hindman's right.

Herron opened an intense two hour artillery barrage on the

Confederate position singling out individual Confederate cannon

and concentrating on taking them out of action one at a time. By

noon, the devastating barrage had disabled most of the

Confederate artillery and forced many of the Confederate troops

to shelter on the reverse slopes.

Seeing the effect of his

artillery, Herron ordered an advance on the hill rather than

waiting for Blunt to arrive. His troops first encountered

Confederate cavalry in the Borden wheatfield at the base of a

ridge overlooking the prairie. Herron took these advanced

troopers to mean that Hindman was planning to attack and capture

the Union artillery. So Herron sent forward two regiments from

his own 3rd Division to assault a Confederate battery near the

Borden house. When his men arrived on the hill they found

themselves under a fierce Confederate counterattack from three

sides by Maramaduke and Brigadier General Francis A. Shoup. Half

of the attacking Federals were wounded or killed within minutes,

most near the Borden House.

Borden House on the Prairie

Grove Battlefield

As the surviving Federals

rolled back down the hill toward the safety of Union lines,

Confederate soldiers spontaneously pursued and attempt to break

Herron's lines. Herron's artillery loaded with canister caused

terrible damage to the unorganized Confederates and repulsed

their attack.

Herron feared the

Confederates would make another rush at his artillery and

preemptively ordered another charge. This time two regiments

were selected from Daniel Huston's 2nd Division. Again near the

Borden house, hand to hand fighting ensued. The Federal troops

repulsed one counter attack before falling back towards Herron's

artillery. Again the pursuing Confederates rushed the Union guns

but were repulsed by troops from Colonel William W. Orme's

brigade.

Meanwhile, Blunt realized

that Hindman had gotten past his flank and intercepted Herron.

Furious, he ordered his men to march to the sound of the guns.

Not knowing the precise location of the fighting, the Federal

troops ignored roads and traversed through farm fields and over

fences straight toward the sound of battle at the double quick.

This movement was probably initiated by Colonel Thomas Ewing and

the 11th Kansas Infantry. While Blunt did not order the maneuver

he quickly endorsed it even chastising a regimental commander

for not showing enough initiative when he failed to follow the

unorthodox procedure. Blunt's forces arrived on the

field just as Hindman was ordering another attack on Herron's

forces. Blunt's division slammed into the surprised Confederates

and drove them back onto the hill. The heaviest casualties of

the battle were felt during this attack by the 10th Missouri

Confederate Infantry, which was caught in the open, at the flank

of the Confederate forces. Blunt aligned his two brigades and

sent them forward toward the Morton house on the same ridge to

the west of the Borden house. Blunt's forces fought somewhat

sporadically until being recalled off the ridge. Mosby M.

Parsons' Rebel brigade swept across the farm fields of prairie

toward Blunt's artillery. Once again the Union soldiers and

artillery repulsed the attack and darkness put an end to the

fighting.

During the night of 7 December

and 8 December Blunt began to call up his reserves. Hindman on

the other hand had no reserves remaining, was low on ammunition

and food, and had lost much of his artillery firepower. Hindman

had no choice but to withdraw under cover of darkness back

towards Van Buren, Arkansas. The Confederates reached Van Buren

on 10 December, demoralized, footsore, and ragged.

By 29 December Blunt and Herron

would threaten Hindman at his Van Buren sanctuary and drive him

from northwest Arkansas permanently.

Federal forces suffered

1,251 casualties and Confederate forces suffered 1,317

casualties. In addition, Confederate forces suffered from severe

demoralization and lost many conscript soldiers during and after

the campaign.

Though the battle was a

tactical draw, it was a strategic victory for the Federal army

as they remained in possession of the battlefield and

Confederate fortunes in northwest Arkansas declined markedly

from that point on.

The Muster Roll for

January-February 1863 notes that John W. Duggins was “absent”

for “detached service.” In February, he is listed as “sick in

hospital.”

Co. E 5th Missouri

Cavalry

Company Muster Roll

January – February 1863

Regimental Roster

February 1863

One month later, on January 29th

1863, John W. Duggins was captured in Howell County, Missouri

and received at Gratiot Military Prison, St. Louis, MO on

February 8, 1863.

“ J. W. Duggins,

Gordon’s Regiment, Appears on a Roll of Prisoners sent to St.

Louis, Mo. by Major Gust. Heinrichs, Provost Marshal Gen., Army

S.E. Mo., at West Plains, Howell Co. Mo., February 3, 1863. Age

23; height 5 feet 7 inches. Remarks: of Saline Co. Mo. Served

in Rebel Army of___ Gordon’s Regt__in battle of _aizy ___.”

Gratiot

Street Military Prison

Gratiot Street Prison

served as McDowell Medical College before the war. The head of

the college, Dr. Joseph McDowell, was well known in the St.

Louis community as a doctor. He was also known for his strange

behavior and outspoken support for the South. Dr. McDowell

acquired two cannons that he kept at his college. He would

instruct his students to fire them on holidays. On one such

holiday he dressed in a colonial-style three-cornered hat and

instructed his students to “make Rome howl.”

When the war broke out,

McDowell made his way to the Confederacy, taking his cannons

with him. As with many known Southern sympathizers his property

was taken and became a barracks. Not long after, word came that

2,000 prisoners of war were on their way to St. Louis. A new

facility was needed when Myrtle Street Prison became

overcrowded. The McDowell Medical College building became

Gratiot Street Prison in December 1861.

During the Civil War

Gratiot Street Military Prison was operated in St. Louis,

Missouri by the Union army. Gratiot was unique in that it was

used not only to hold Confederate prisoners of war, but spies,

guerillas, civilians suspected of disloyalty, and even Federal

soldiers accused of crimes or misbehavior. The prison also was

centered in a city of divided loyalties. Escapees could find

refuge in homes not even half a block away. Many of the most

dangerous people operating in the Trans-Mississippi passed

through its doors. Some escaped in dramatically risky ways;

others didn't and lost their lives at the end of a Union rope,

or before a firing squad.

It was right in the

midst of some of the wealthiest homes in St. Louis. General

Fremont's headquarters in the Brant Mansion were only a block

away. Right across the street was the home of the wealthy

Harrison family. Attached to Gratiot on the north was the

Christian Brothers Academy. The biggest single escape was in

December 1863 when about 60 men escaped through a tunnel. Others

cut through the wall into Christian Brothers Academy where they

were--without hindrance--shown the exit. This is not to say

escapes came easily or without cost--a sizeable number were

killed in the attempts and others thwarted. Being in the

location it was, in the midst of often sympathetic houses, made

it easier to make good an escape. A safe hiding place could be

found often as near as half a block from the prison.

Most of the dead

prisoners were buried at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

Some were claimed by families and taken home for burial.

Some--particularly smallpox victims--were buried in cemeteries

at the smallpox hospitals or on a Quarantine Island in the

middle of the Mississippi River.

The location is now the

headquarters of Ralston-Purina and has been for over a century.

The original Gratiot building was demolished in 1878.

|

Statement

of John W Duggins a Prisoner at the

Gratiot St. Prison, St. Louis made the 12 day of

February 1863.

My age is 22 years.

I live in Saline County, Missouri.

I was born in " County Missouri

I was captured in near West

County Plains, Missouri

On or about the 28 day of January 1863

The cause of my capture was

that I was a con

federate soldier, left behind

by my command, sick.

I was in arms against the

United States, and was a [rank] Private

in E Company Gordon's Regiment Cavalry

I was sworn into the Rebel service about the

17th day of Aug. 1862 by Jos Shelby

in LaFayette County, Missouri, for an years

in

definite period.

When captured, I was

taken in West Plains and remained

there about three days and was

examined there by the Prison and was sent to Gratiot

Prison about the 8 day of February 1863

I do not wish to

be exchanged.

Selected by the Prisoner,

the day

first named, in my presence

|

|

The Prisoner makes

additional statements as follows, in answer to

questions: 1. How

many times have you been in arms during the rebellion?

One

2. What commanders have you served under?

Gordon

3. What battles or skirmishes have you been in?

Pilot Grove

4. Did you have arms, or were you out on picket,

or what part did you take in the action?

I had arms but

did not fight

5. Have you ever furnished arms or ammunition,

horse, provisions, or any kind of supplies to any rebel?

State when, where and how often.

Never

6. Was there any rebel camp near you, that you

did not give notice to the U.S. troops?

7. Have you ever been with any one taking or

pressing horses, arms or other property?

No

8. Are you enlisted in the E.M.M. - loyal or

disloyal?

No

9. Are you a southern sympathizer?

No

10. It's your sincere desire to have the southern people

put down and the authority of the U.S. Government over

them restored?

Yes, by force if

necessary. |

|

11. How many slaves have

you? None

12. Have you a wife - how many children.

Single

13. What is your occupation? Farming

14. What relatives have you in this rebellion?

No near ones that

I know of

15. Have you ever been in any Rebel camp? If so,

whose - when, where and how long? What did you do? Did

you leave it or where you captured in it?

I was sworn

in by Shelby as he said

"to put down some bushwhacking and horse

stealing." He never

stopped after we started

once he got us down to

Arkansas. I was en-

listed by false represent

ations, and wish now to

be released on oath and

bond and if necessary in

volvement. Shelby told us

that Davis was in Johnson

Co. burning houses and killing

women and children

John W. Duggins

Submitted before

me Feb 12, 1863 |

|

|

Prison Papers dated

March 18, 1863

What is your age. 22 years

I live in Saline County Mo

When were you taken prisoner

27 of January in Howell Co. Mo

by the 11 Wisconsin

How long have you been in this prison) 6 weakes

Have you ever been examined yes

When and where were you examined

in this place

Are you a man of family I am

not

Why were you taken prisoner

because I was a

Confederate

Soldier

What terms do you ask to be relea

sed on

take

the oath and give

bond and trial if necessary

John W. Duggins |

On April 24, 1863 Private Duggins was

released from Gratiot Military Prison on oath and bond of $2000

Bartels, "Trans-Mississippi

Men", p. 134, shows that John W. Duggins, enlisted as a

private in Company H, Slayback's MO Cavalry Regiment, November

1864, Thus it is apparent that he went with the army when it

passed through the area during Price's Missouri Raid in the fall

of 1864, and doubtless left the state with the army.

Slayback's Missouri Battalion participated in

more than fifteen various type engagements during its career. By

the time John William Duggins had re-enlisted (breaking his

oath) the battalion was greatly reduced and broken down by the

hardships of the campaign. The battalion retreated into the

Indian Territory, wintering there in the winter of 1864-1865. In

early 1865 the unit appears to have divided into at least three

small detachments. One of these moved to Shreveport, Louisiana,

where the Army of Trans-Mississippi had been consolidated.

This detachment

was included among the Confederate Trans-Mississippi troops

surrendered in early June, 1865. It is probable that it had

ceased to exist before that date, disbanding when the news of

the collapse of the eastern half of the Confederacy was

received. A second detachment was scouting near Pine Bluff,

Arkansas, when it learned of the surrender of the eastern

Confederacy. It appears to have surrendered to a detachment of

Kansas Militia at Pine Bluff on May 28, 1865. The third

detachment disbanded in southeastern Arkansas in early June,

1865. It is not known to which detachment John Duggins belonged.

On September 4, 1865,

John W. Duggins married Artemisia E. Hawkins. She was born

August, 19 1845. John and Artemisia had six children:

-

LUNA B. DUGGINS, b. 1866

-

OLLIE V. DUGGINS, b. 1868

-

SUSIE M. DUGGINS, b. 1871

-

KATE V. DUGGINS, b. 1873

-

JOHN T. DUGGINS, b. 1876

-

SPENCER M. DUGGINS, b. 1879

Twenty years after the

close of the Civil War, Higginsville, Missouri was the scene of

a re-union of the veterans of the Confederacy on Tuesday, August

25, 1885. Listed among the participants from Joseph Orville’s

Shelby’s Command was John William Duggins, Pvt. Co. E,

Gordon’s.

In 1892, John ran for the

office of County Assessor for Saline County. It is not known if

he was successful.

John William Duggins died December 3, 1902 in

Hammond, Louisiana, at 63 years of age. Artemesia E. Hawkins

died November 8, 1917 in Calloway County, MO.

Headstones of

John W. Duggins

(left) and

Artemisia E. Hawkins (right)

Good Hope Cemetery

Cambridge, MO

|