|

Dive Log

Back to

Back to

|

Grand

Cayman, British West Indies

July, 1980

Selecting a dive package is like going to a

smorgasbord; there are numerous selections and potential risk.

Area dive shops invariably offer island dive trips to Cozumel or

the Bahamas and that's fine if you like to go with a large group

to commercial dive resorts. But that defeated the purpose

of learning a sport that can put you anywhere in the world.

Or it may be that we were too much the loners to be associated

with large groups.

|

Our

selection criteria for dive locations was generally

based on inaccessibility of large cruise ships - no deep

sea port, limited/small dive operation, basic lodging

accommodations, etc. We subscribed to a number of

diving magazines all advertising destinations with

pristine diving and memories of a lifetime.

We settled on Grand Cayman for our

first saltwater dive adventure. The advertisements

boasted of seven miles of white sand beaches,

continental dining, a fresh water pool, two bars, and a

dive shop on the premises.

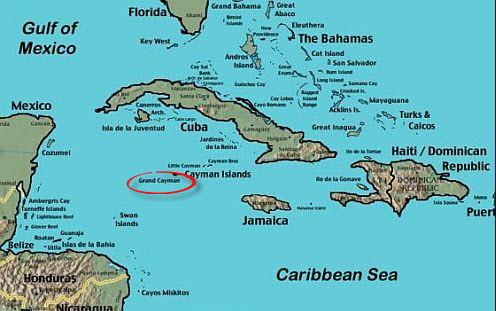

Grand Cayman is the largest of the three Cayman Islands

and the location of the territory's capital, George

Town. In relation to the other two Cayman Islands, it is

approximately 75 miles southwest of Little Cayman and 90

miles southwest of Cayman Brac.

|

|

A bit of history...

Christopher Columbus sighted the Cayman Islands (after the Carib

word caimán for the marine crocodile ) on May 10, 1503

and found the two small islands (Cayman Brac and Little Cayman)

and it was these two islands that he named "Las Tortugas".

The first recorded English visitor was Sir Francis Drake in

1586, who reported that the caymanas were edible, but it

was the turtles which attracted ships in search of fresh meat

for their crews. Overfishing nearly extinguished the turtles

from the local waters.

Caymanian folklore explains that the island's first inhabitants

were a Welshman named Walters (or Watler) and his companion

named Bawden (or Bodden), who first arrived in Cayman in 1658

after serving in Oliver Cromwell's army in Jamaica. The first

recorded permanent inhabitant of the Cayman Islands, Isaac

Bodden, was born on Grand Cayman around 1700. He was the

grandson of the original settler named Bodden.

A

variety of people settled on the islands: pirates, refugees from

the Spanish Inquisition, shipwrecked sailors, and slaves. The

majority of Caymanians are of African and English descent, with

considerable interracial mixing.

England took formal control of the Caymans, along with Jamaica,

under the Treaty of Madrid in 1670 after the first settlers came

from Jamaica in 1661-71 to Little Cayman and Cayman Brac. These

first settlements were abandoned after attacks by Spanish

privateers, but English privateers often used the Cayman Islands

as a base and in the 18th century they became an increasingly

popular hideout for pirates, even after the end of legitimate

privateering in 1713. Following several unsuccessful attempts,

permanent settlement of the islands began in the 1730s. The

Cayman Islands historically have been popular as a tax haven. In

November 1794, ten vessels, which were part of a convoy escorted

by HMS Convert, were wrecked on the reef in Gun Bay, on the East

end of Grand Cayman, but with the help of local settlers, there

was no loss of life. The incident is now remembered as The Wreck

of the Ten Sail. Legend has it that there was a member of the

British Royal Family onboard and that in gratitude for their

bravery, King George III decreed that Caymanians should never be

conscripted for war service and Parliament legislated that they

should never be taxed.

From 1670, the Cayman Islands were effective dependencies of

Jamaica, although there was considerable self-government. In

1831, a legislative assembly was established by local consent at

a meeting of principal inhabitants held at Pedro St. James

Castle on December 5 of that year. Elections were held on

December 10 and the fledgling legislature passed its first local

legislation on December 31, 1831. Subsequently, the Jamaican

governor ratified a legislature consisting of eight magistrates

appointed by the Governor of Jamaica and 10 (later increased to

27) elected representatives.

In 1835, Governor Sligo arrived in Cayman from Jamaica to

declare all slaves free in accordance with the Emancipation Act

of 1833.

The Cayman Islands were officially declared and administered as

a dependency of Jamaica from 1863, but were rather like a parish

of Jamaica with the nominated justices of the peace and elected

vestrymen in their Legislature. From 1750 to 1898 the Chief

Magistrate was the administrating official for the dependency,

appointed by the Jamaican governor. In 1898 the Governor of

Jamaica began appointing a Commissioner for the Islands. The

first Commissioner was Frederick Sanguinetti. In 1959, upon the

formation of the Federation of the West Indies the dependency

status with regards to Jamaica ceased officially although the

Governor of Jamaica remained the Governor of the Cayman Islands

and had reserve powers over the Islands. Starting in 1959 the

chief official overseeing the day-to-day affairs of the islands

(for the Governor) was the Administrator. Upon Jamaica's

independence in 1962, the Cayman Islands broke its

administrative links with Jamaica and opted to become a direct

dependency of the British Crown, with the chief official of the

islands being the Administrator.

Following a two-year campaign by women to change their

circumstances, in 1959 Cayman received its first written

constitution which, for the first time, allowed women to vote.

Cayman ceased to be a dependency of Jamaica.

In 1971 the governmental structure of the Islands was again

changed with a Governor now running the Cayman Islands.

|

As was customary at the time with many

international flights, our trip to Grand Cayman required a

layover. For us, that meant a tiresome sit in a Texas

airport. From Texas we flew Antillian Airways -

serving complimentary rum punch before landing.

Although landing on Grand Cayman Island

was more spacious than most islands we have been to, it still

felt as though the pilot had put his landing gear down on the

very edge of the island, went immediately to full flaps, brakes,

and stopped not 15 feet from the end of the runway and the

ocean.

In 1980, the Grand Cayman International

Airport consisted of a Customs Office, baggage room, and a

sitting room. We were checked through customs after a few

preliminary questions and a quick search of our luggage.

Taxis were numerous and one had been sent by our hotel to pick

up any and all passengers...and any natives traveling that

direction. The drive was a young black man who was very

courteous and seemed willing to answer all our questions.

Our hotel was the Royal Palms, situated

ideally on the seven miles of white sands advertised in the dive

magazine.

It it's hey day, the hotel must have been

spectacular with it's white concrete entrance, avenue of mature

palm trees, and its stately open appearance. And although

it showed evidence of wear, it still retained an air of dignity

and of conspicuous consumption.

The Royal Palms today is once again a

highly rated destination.

We checked in on a Sunday afternoon and

were given a brief tour of the facilities. Our room was on

the second floor of one of the older wings overlooking the pool

and courtyard. After settling in, we anxiously went to

inquire about our diving arrangements which were included as

part of the package. We were informed that the dive shop

was closed, and it was too late to make arrangements to dive the

following day.

We inquired if there was another dive

operation that may be able to help; "Well just down the

street there's a dive shop run by Bob Soto."

|

Bob Soto, established the

Caribbean’s first dive operation on Grand Cayman in

1957.

Soto’s introduction into diving came during World War II

when he went to work in the United States for the US

Navy. He started as a diver tender on a salvage

tug, progressing to assistant diver and then to hard hat

diver. After the war, Soto joined the Merchant Marines,

giving him the opportunity to dive in many places, such

as the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and the waters off

South America. Returning home he realized that the

underwater scenery in Cayman was ‘second to none’.

Soto established a diving school in the Cayman Islands

for the tourism market. Soto created his own

equipment and promotional diving videos to assist the

Cayman Islands Department of Tourism and diving clubs

throughout the United States, as well as introducing the

first “live-aboard” trips. |

|

Soto, known as the “father of diving,” continues his

interest in marine and environmental conservation and

was instrumental in marine laws being put in place in

1986. He is very knowledgeable of the development

of these islands and the constant geographical movement

of the land and the sea. He continues to campaign

for more stringent laws to try and preserve marine life.

In 1996 he was given the ‘Marine Conservation Award’ for

his valiant efforts. Soto was made a Member of the

British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II for his various

life-long contributions. |

So off we walked towards Georgetown which

was a hike of 20 minutes or so, and one we would make

frequently. The shop was easily located and we inquired

within about arrangements for the following day. A

double-decked pontoon would pull up on the beach in front of our

hotel the next afternoon on their way to a dive spot with other

Soto divers on board.

We slept very little in anticipation of

our first saltwater dive, but we were raring to go in the

morning.

We were scheduled that afternoon to dive

Fish Pot Reef, just off Georgetown. The air temp was a

marvelous 95 with clear skies. This was the first time I

ever swam in saltwater. My heart was a flutter. This

is what it was all about!

The Dive Master gave an explanation of the

reef saying that we would be diving through tunnels of coral.

We entered the water at 2:55 PM. Visibility ran anywhere

from 90 to 100 feet with massive outcroppings of live coral

bordered by shoots of white sand. No words can adequately

describe the beauty.

There were brain coral six feet in radius.

Stag horn and elk horn reefs. And everywhere there were

fish too numerous to name and too many to catch in one glance.

Then fate stepped in to create another first.

On my first dive trip, on my first dive,

within the first ten minutes, I cut myself. We had been

going through several tunnels and I had just turned around to

check on Dad when I hit the palm of my hand on a piece of shelf

coral. The cut was a clean and deep "V" on my right hand.

It immediately began to bleed blue blood.

Perhaps I should explain. At different depths, colors are

lost to filtrating light. Red is one of the first colors

to go, so I was bleeding blue. I closed the wound with my

left hand and, showing it to Dad, I indicated that I did not

want to stop the dive. We surfaced 40 minutes later after

an otherwise tremendous dive. It was everything I had

hoped for.

After surfacing, it was impossible to

climb into the boat and remove my gear without releasing the

pressure on the wound. And being wet, the cut bled

profusely. The Dive Master cut a towel to make a wrapping

and by elevating my hand it bled very little. The only

pain was my pride. The return boat trip seemed much longer

with the numerous inquiries from the other divers.

Upon return to our hotel room and with

closer examination of the cut, Dad thought it should be stitched

and I agreed. We inquired in the lobby how to get to the

hospital and called for a cab. Still wrapped in the bloody

yellow beach towel, we headed for the "Casualty Room" - the

islands equivalent to an emergency room.

The concrete block building appeared

inside and out to be more like a bath house than a hospital.

The benches in the "Waiting Room" were also concrete built into

the walls and without padding. There was an "Admittance"

window at which we related for the umpteenth time how I had cut

my hand and were told to take a seat and wait.

There were fewer than half a dozen

patients in the room waiting for shots and prescriptions.

It was just after 5 PM when we were asked by the nurse to step

into the "Examination Room". She and several other, what

appeared to be nurse aids, examined the exposed flap of skin and

deliberated on whether or not the flap should be cut away and

allowed to heal on its own or stitched. Thank goodness, it

was decided that the nurse should contact the doctor who had

just gone to dinner and wouldn't be back for another hour.

So, we waited in the "Operating Room".

The room was unbelievable. In it

were chests with instruction sheets posted for the treatment of

numerous injuries. There was one gurney about five feet

long with two tanks at its head. The sheets were bloody

and the swabs and wrappings from the previous operation were

still on the floor. There was one air conditioner in the

only window running at full speed but making little headway.

To top it all off, we spent the the time waiting watching a

colony of ants drag dead butterflies across the floor.

The doctor arrived promptly one hour

later. he was in his late twenties or early thirties with

a reddish beard and curly hair and very English. We

learned that he was educated in England and interned on the

island.

After examining the cut, he concluded that

it would require stitching. The hand needed to be placed

on a flat surface and the only way to do that was to sit in a

chair next to the gurney, rotate my arm backwards and lay it on

the table behind my back. The shot of novacane as given

locally using a glass hypodermic with a LONG needle. The

doctor's hands shook slightly but the area was already somewhat

void of feeling. He then asked the nurse for 2-O silk.

"We don't have any." Then 3-0. "We don't have any."

They settled for black 4-O that I swore you could string a

tennis racket with.

Finishing with six stitches, he wrapped

the hand and said that he knew we were divers and it wouldn't do

any good to tell me not to get the stitches wet, but to dry the

hand off as quickly as I could after the dive. He wrote a

prescription for pain which we could get filled at the local

drug store. We thanked him and returned to the office to

pay our bill.

The island, being under British rule, had

socialized medicine. We asked the office clerk how much

the surgery cost. The girl said she didn't know but they

would send us a bill. We explained that we were from the

United States, but that didn't seem to make any difference.

A bill did arrive several weeks after our return. Fir the

stitches, removal of the stitches, the first prescription, and

medication, the cost was $17 if we paid by cash and $13 if we

paid by check.

The night was very restless when the

injection wore off and all the nerve endings came to life.

Come morning, there was no pain whatsoever. However, we

didn't think it would be wise to dive that day. Our plan

was to go into town and purchase a latex glove and surgical tape

to seal the water out. We purchased the only box of large

Playtex gloves the store had along with some tape and spent the

remainder of our time in Georgetown shopping. We bout a

couple of sharks carved from black coral and I bought an antique

Spanish piece of two (Spanish Reales were minted in 1/2s, 2s,

4s, and 8s - the legendary pieces of 8).

The remainder of the day we spent touring

the island. The hotel recommended a driver/guide named

Ruby. Ruby knew everyone on the island, or at least she

stopped and talked to everyone along the way. As a source

of information, Ruby was a gem. We stopped and sampled

native fruits from people's gardens; she was well versed in

native vegetation and the history of the island. Ruby

literally drove is to Hell and back.

|

Hell,

at least in the islands, has a make-shift post office

complete with an official stamp (Hell, BWI). It is

not a town. It is an outcropping of strange

volcanic formations; like stalagmites of upward

projecting jagged spears of lava. If ever there

were in nature a depiction of Hell, Dante must surely

agree that this is it. We sent Mother a postcard

from Hell just to say we had been there and back.

Hell Post Office with Dad

in the foreground and Ruby in the background |

In 2012, my brother and his wife went to

Hell. The Post office had changed considerably.

Included in our tour of the island was a

visit to the Grand Cayman Turtle Farms.

Cayman Turtle Farm was established in 1968 as Mariculture Ltd.

by a group of investors from the United States and Great Britain

as a facility to raise the green sea turtle for commercial

purposes. The intention was to supply the market with a source

of product that did not deplete the wild populations further. By

releasing turtles and facilitating research, any harm created by

removing turtles and eggs from the wild would be mitigated.

When were were there, the farm consisted

of a collection of holding tanks and nurseries operating much

like a fish hatchery. The Mexican government had an

ongoing study of an endangered species of sea turtle at the farm

although the guide didn't seem interested in talking about it.

The gift shop had a number of attractive

and attractively priced gifts from turtle shell glasses,

coasters, table tops, and polished shells to mummified/dried

baby sea turtles. We purchased some hand lotion for Mother

made from sea turtle oil. As it turned out, it was wise

that we didn't buy any other products since there was a ban on

articles made from sea turtles and they would have been

confiscated at US Customs; I have a polished sea turtle shell

undoubtedly adorning the wall of a customs storeroom to attest

to the fact.

Today, the Turtle Farm is a major tourist

attract with pools, wildlife encounter areas, water park, shows,

etc.

Having recovered from my coral encounter

and have had a day to rest, we began to plan for the morning

dive. We opened the box of rubber gloves only to find that

it contained two left-hand gloves and my cut was on the right

hand. Years of expensive education didn't go to waste, the

obvious solution was to turn the glove inside out.

The scheduled morning dive was to "Shark's

Hide" off Georgetown noted for the basket and barrel sponges

that are large enough to stand in. The weather was clear

and warm with water visibility up to 100 feet. I slipped

on the glove and taped it into place. We donned our tanks

and in we went - and in came the water into the glove. Oh

well. The dive consisted of a coral wall leading to the

open sea. Our average dept was 80 feet for a total dive

time of 20 minutes. All-in-all it was a great dive.

Sometime during the week - I don't remember

which day - we visited the ruins of the salt pans. African

slaves were imported to work the pans because the indigenous

Indians were too small to handle the burdensome loads. The

slaves were housed in huts shaped in a cube 6 feet by 6 feet

with a height of 4 feet. The huts were too small to stand

in or sleep comfortably. Several roofless huts still

remained as do the pans which were originally filed with sea

water and allowed to evaporate. The remaining salt was

harvested and shipped around the world.

Today, sea salt is still harvested from pans

and exported.

This being our first trip to the Islands, it

was also our first exposure to "island time." Being

regimented to time schedules and accustomed to looking at a

watch or clock every few minutes, we found ourselves waiting - a

lot. Other than the scheduled departure of the dive boat,

there is no sense of time and the natives move at an almost

sloth pace. Time is, "whenever" - whenever they feel like

it. Mangers have learned that giving a list of chores to

workers is useless. it is better to give them one task to

do and when completed they give them another. My advise to

divers is to take a dive watch and leave it with your gear at

the end of the dive. We made a

number of dives to reefs with exotic names - Eden Rock, Drop

Off, Island Shoot, and Surfside Reef - before diving our first

wreck; the Oro Verde.

|

The

184' Oro Verde (meaning green gold) was a liberty tanker

sunk in May 31, 1980 to serve as a dive site and as a

base for a reef. The ship lays on its

starboard side in about 50 feet of water, easily

accessible from a dive boat. The hull was left

open for fish and divers to explore. Not the

Spanish galleon one would hope to dive, but interesting

nonetheless.

|

The boat was just beginning

to attract colonies of fish including one large

angel fish with a hole through its body - the

result a a spear gun. It obviously didn't

hold a grudge since it was first to the

breadline; bread being taken down in plastic

bags by the Dive Master to feed the fish. |

|

| A quick

explanation of the operations on a dive boat might be in

order for the uninitiated. Dive boats range from

pontoons to strafed-hulled open cockpit boats, to wooden

launches, to cabin cruisers. Anything that floats

and has a motor to transport divers in some relative

safety and comfort to a dive site will fulfill the dive

boat requirement. The FLAG Diving operation that

we used from the hotel operated two double-decked

pontoons with a walk-on bow and a platform at the stern

to enter and exit the water. Each boat normally

had two operators; one piloted the boat and may or may

not also dive with the group, the second was the Dive

Master who oversaw the dives.

Our Dive Master was a young man named

Derrick whose father was in the fishing industry in

Texas. The duties of the dive boat personnel were

many - skipper, mechanic, dock hand, pilot, social

worker, and instructor. The boats were usually

equipped with tanks so we carried only our personal gear

on board - mask, fins, snorkel, regulators, and buoyancy

control device (BC).

For the most part, the dive sites

were marked with permanent moorings. Where there

were no moorings, the crew were VERY careful to make

certain that we anchored in a sand shoot to not damage

the coral. |

At 10:47 AM we climbed out of the

water from our last dive of the year and our first

saltwater dive adventure. We packed our bags and

taxied to the airport that afternoon for the flight

home.

The final note in the

dive log

says it all;

"Last Dive - Great Week -

Fantastic Diving!!!" |

Trinity Caves was a unique dive.

It was like diving a cave except that the coral formed

the stalactites and stalagmites. I kept my hands

to my side this time.We

made one last trip to George Town to pick up a few

souvenirs and to stop by the hospital to have my

stitches removed. This trip began a long tradition

of collective dive T-shirts. The collection of

shirts from various islands inevitably sparked

conversations.

The last dive of any trip is the

most difficult; you want it to last as long as possible.

Our last dive was at Flamingo Tongue; a large coral reef

in 30 feet of water. The reef is named after the

snail that inhabits the waters.

|

Back to

Back to

|