|

PRINT Version

Magna Carta

Surety Baron

Ancestors

PRINT Version

of this article

Link to

The National Society

Magna Charta Dames

and Barons

Back to

|

INTRODUCTION

On the 15th

of June, 1215, King John met his Barons on the field of

Runnemede, the ancient meadow of council. His followers were

few as he met more than two thousand Knights and Barons in arms

encamped on the field. The Barons had sworn an oath that they

would compel the King to confirm their liberties or they would

wage war against him to the death. Theirs was a holy crusade

against John to recover the liberties their forefathers had

enjoyed and to restore the good old customs violated by an

oppressive and mercenary ruler. Their demands had been

presented to the King months before for his consideration, and

before the day passed he affixed his seal to the original but

preliminary draft known as the "Articles of the Barons." The

exact terms of the Great Charter itself were decided and

engrossed during four subsequent days of negotiation, and it was

on the 19th that the great seal was affixed to all copies. These

were all dated back to the 15th of June, and duly sealed by the

King.

The Great Charter of Liberties has

become The Mother of Constitutions. The liberties of half the

civilized world are derived from the English Magna Carta. It is

recognized as the basis of our laws, and of national liberty in

general. Long standing customs, called Common Law, had now

become written law, among them, no taxation without

representation, judgment by peers, and due process of law.

Liberty is the keynote of the Charter, to have and to hold, to

them and their heirs, for ever. The King is not above the law;

the law reigns supreme.

The eight Surety

Barons profiled in this report along with King John of England

are all ancestors. The lineage from each is shown to the side

to make it easier for the reader to comprehend.

|

Seal of King John |

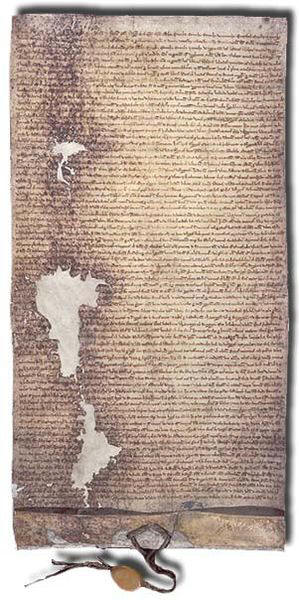

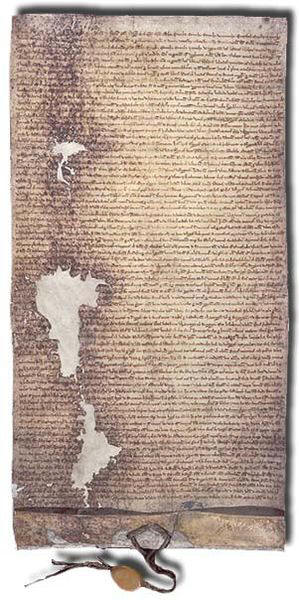

Magna Carta

(Latin for "Great

Charter", literally "Great Paper"), also called Magna

Carta Libertatum ("Great Charter of Freedoms"), is an

English charter originally issued in 1215. Magna Carta

was the most significant early influence on the long

historical process that led to the rule of

constitutional law today. Magna Carta was originally

created because of disagreements between Pope Innocent

III, King John and his English barons about the rights

of the King. Magna Carta required the king to renounce

certain rights, respect certain legal procedures and

accept that the will of the king could be bound by

law.

There are a number

of popular misconceptions about Magna Carta, such as

that it was the first document to limit the power of an

English king by law (it was not the first, and was

partly based on the Charter of Liberties); that it in

practice limited the power of the king (it mostly did

not in the Middle Ages); and that it is a single static

document (it is a variety of documents referred to under

a common name).

Magna Carta was

renewed throughout the Middle Ages, and further during

the Tudor and Stuart periods, and the 17th and 18th

centuries. By the early 19th century most clauses had

been repealed from English law. The influence of Magna

Carta outside England can be seen in the United States

Constitution and Bill of Rights. Indeed just about every

common law state has been influenced by Magna Carta,

making it one of the most important legal documents in

the history of democracy.

Events leading to Magna Carta

After the Norman

Conquest of England in 1066 and advances in the 12th

century, the English king had by 1199 become the most

powerful monarch in Europe. This was due to a number of

factors including the sophisticated centralized

government created by the procedures of the new

Anglo-Saxon systems of governance, and extensive

Anglo-Norman land holdings in Normandy. But after King

John was crowned in the early 13th century, a series of

stunning failures on his part led the barons of England

to revolt and place checks on the king's power.

France

One major cause of

discontent in the realm were John's actions in France.

At the time of John's accession to the throne after

Richard's death, there were no set rules to define the

line of succession. John, as Richard's younger brother,

was crowned over Richard's nephew, Arthur of Brittany.

As Arthur still had a claim over the Anjou empire,

however, John needed the approval of the French King,

Philip Augustus. To get it, John gave to Philip vast

tracts of the French-speaking Anjou territories. |

When John later married

Isabella of Angoulême, her previous fiancé (Hugh IX of Lusignan,

one of John's vassals) appealed to Philip, who then declared

forfeit all of John's French lands, including the rich Normandy.

Philip declared Arthur as the true ruler of the Anjou throne and

invaded John's French holdings in mid-1202 to give it to him.

John had to act to save face, but his eventual actions did not

achieve this—he ended up killing Arthur in suspicious

circumstances, thus losing the little support he had from his

French barons.

After the defeat of John's

allies at the Battle of Bouvines, Philip retained all of John's

northern French territories, including Normandy (although the

Aquitaine remained in English hands for a time). As a result,

John was revealed as a weak military leader, and one who lost to

the French a major source of income, neither of which made him

popular at home. Worse, to recoup his expenses, John would have

to further tax the already unhappy barons.

Note: John's nickname of "Lackland"

does not refer to these losses to France, but to the fact that,

unlike his elder brothers, he had received no land rights on the

continent at birth.

The Church

At the time of John’s reign

there was still a great deal of controversy as to how the

Archbishop of Canterbury was to be elected, although it had

become traditional that the monarch would appoint a candidate

with the approval of the monks of Canterbury.

But in the early 13th

century, the bishops began to want a say. To retain control, the

monks elected one of their numbers to the role. But John,

incensed at his lack of involvement in the proceedings, sent the

Bishop of Norwich to Rome as his choice. Pope Innocent III

declared both choices as invalid and persuaded the monks to

elect Stephen Langton, who in fact was probably the best choice.

But John refused to accept this choice and exiled the monks from

the realm. Infuriated, Innocent ordered an interdict (prevention

of public worship) in England in 1208, excommunicated John in

1209, and backed Philip to invade England in 1212.

John finally backed down

and agreed to endorse Langton and allow the exiles to return,

and to completely placate the pope he gave England and Ireland

as papal territories and rented them back as a fiefdom for 1,000

marks per annum. This further enraged the barons as it meant

that they had even less autonomy in their own lands.

Taxes

Despite all of this,

England's government could function without a strong king. The

efficient civil service, established by the powerful King Henry

II had run England throughout the reign of Richard I. But the

government needed money, for during this period of prosperity

mercenary soldiers cost nearly twice as much as before. The loss

of the French territories, especially Normandy, greatly reduced

the state income and a huge tax would have to be raised in order

to attempt to reclaim these territories. Yet it was difficult to

raise taxes due to the tradition of keeping them at the same

level.

Novel forms of income

included a Forest law, a set of regulations about the king’s

forest which were easily broken and severely punished. John also

increased the pre-existing scutage (feudal payment to an

overlord replacing direct military service) eleven times in his

seventeen years as king, as compared to eleven times in twice

that period covering three monarchs before him. The last two of

these increases were double the increase of their predecessors.

He also imposed the first income tax which rose, what was at the

time, the extortionate sum of £60,000.

Rebellion

and civil war

By 1215, some of the barons

of England banded together and took London by force on June 10,

1215. They and many of the fence-sitting moderates not in overt

rebellion forced King John to agree to a document called the

"Articles of the Barons", to which his Great Seal was attached

in the meadow at Runnymede on June 15, 1215. In return, the

barons renewed their oaths of fealty to King John on June 19,

1215. A formal document to record the agreement was created by

the royal chancery on July 15: this was the original Magna Carta.

An unknown number of copies of it were sent out to officials,

such as royal sheriffs and bishops.

The most significant clause

for King John at the time was clause 61, known as the "security

clause", the longest portion of the document. This established a

committee of 25 barons who could at any time meet and over-rule

the will of the King, through force by seizing his castles and

possessions if needed. This was based on a medieval legal

practice known as distraint, which was commonly done, but

it was the first time it had been applied to a monarch. In

addition, the King was to take an oath of loyalty to the

committee.

King John had no intention

to honor Magna Carta, as it was sealed under extortion by force,

and clause 61 essentially neutered his power as a monarch,

making him King in name only. He renounced it as soon as the

barons left London, plunging England into a civil war, called

the First Barons' War. Pope Innocent III also immediately

annulled the "shameful and demeaning agreement, forced upon the

king by violence and fear." He rejected any call for rights,

saying it impaired King John's dignity. He saw it as an affront

to the Church's authority over the king and released John from

his oath to obey it.

Magna Carta

re-issued

John died in the middle of

the war, from dysentery, on October 18, 1216, and this quickly

changed the nature of the war. His nine-year-old son, Henry III,

was next in line for the throne. The royalists believed the

rebel barons would find the idea of loyalty to the child Henry

more palatable, and so the child was swiftly crowned in late

October 1216 and the war ended.

Henry's regents reissued

Magna Carta in his name on November 12, 1216, omitting some

clauses, such as clause 61, and again in 1217. When he turned 18

in 1225, Henry III himself reissued Magna Carta again, this time

in a shorter version with only 37 articles.

Henry III ruled for 56

years (the longest reign of an English Monarch in the Medieval

period) so that by the time of his death in 1272, Magna Carta

had become a settled part of English legal precedent, and more

difficult for a future monarch to annul as King John had

attempted nearly three generations earlier.

Henry III's son and heir

Edward I's Parliament reissued Magna Carta for the final time on

12 October 1297 as part of a statute called Confirmatio

cartarum (25 Edw. I), reconfirming Henry III's shorter

version of Magna Carta from 1225.

Content of

Magna Carta

The Magna Carta was

originally written in Latin. A large part of Magna Carta was

copied, nearly word for word, from the Charter of Liberties of

Henry I, issued when Henry I ascended to the throne in 1100,

which bound the king to certain laws regarding the treatment of

church officials and nobles, effectively granting certain civil

liberties to the church and the English nobility.

Rights still

in force today

Clause 1 of Magna Carta

(the original 1215 edition) guarantees the freedom of the

English Church. Although this originally meant freedom from the

King, later in history it was used for different purposes.

Clause 13 guarantees the “ancient liberties” of the city of

London. Clause 39 gives a right to due process.

The 1215 edition was

annulled in 1216 but some of the 1297 version is still in force

today and preserves the rights listed above.

In 1828

the passing of the first Offences Against the Person Act, was

the first time a clause of Magna Carta was repealed, namely

Clause 36. With the document's perceived protected status

broken, in one hundred and fifty years nearly the whole charter

was repealed, leaving just Clauses 1, 13, 39, and 40 still in

force after the Statute Law (Repeals) Act was passed in 1969.

The Magna Carta

(The

Great Charter)

Preamble: John, by

the grace of God, king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of

Normandy and Aquitaine, and count of Anjou, to the

archbishop, bishops, abbots, earls, barons, justiciaries,

foresters, sheriffs, stewards, servants, and to all his

bailiffs and liege subjects, greetings. Know that, having

regard to God and for the salvation of our soul, and those

of all our ancestors and heirs, and unto the honor of God

and the advancement of his holy Church and for the

rectifying of our realm, we have granted as underwritten by

advice of our venerable fathers, Stephen, archbishop of

Canterbury, primate of all England and cardinal of the holy

Roman Church, Henry, archbishop of Dublin, William of

London, Peter of Winchester, Jocelyn of Bath and

Glastonbury, Hugh of Lincoln, Walter of Worcester, William

of Coventry, Benedict of Rochester, bishops; of Master

Pandulf, subdeacon and member of the household of our lord

the Pope, of brother Aymeric (master of the Knights of the

Temple in England), and of the illustrious men William

Marshal, earl of Pembroke, William, earl of Salisbury,

William, earl of Warenne, William, earl of Arundel, Alan of

Galloway (constable of Scotland), Waren Fitz Gerold, Peter

Fitz Herbert, Hubert De Burgh (seneschal of Poitou), Hugh de

Neville, Matthew Fitz Herbert, Thomas Basset, Alan Basset,

Philip d'Aubigny, Robert of Roppesley, John Marshal, John

Fitz Hugh, and others, our liegemen.

1.

In the first place we have granted

to God, and by this our present charter confirmed for us and

our heirs forever that the English Church shall be free, and

shall have her rights entire, and her liberties inviolate;

and we will that it be thus observed; which is apparent from

this that the freedom of elections, which is reckoned most

important and very essential to the English Church, we, of

our pure and unconstrained will, did grant, and did by our

charter confirm and did obtain the ratification of the same

from our lord, Pope Innocent III, before the quarrel arose

between us and our barons: and this we will observe, and our

will is that it be observed in good faith by our heirs

forever. We have also granted to all freemen of our kingdom,

for us and our heirs forever, all the underwritten

liberties, to be had and held by them and their heirs, of us

and our heirs forever.

2.

If any of our earls or barons, or

others holding of us in chief by military service shall have

died, and at the time of his death his heir shall be full of

age and owe "relief", he shall have his inheritance by the

old relief, to wit, the heir or heirs of an earl, for the

whole barony of an earl by £100; the heir or heirs of a

baron, £100 for a whole barony; the heir or heirs of a

knight, 100s, at most, and whoever owes less let him give

less, according to the ancient custom of fees.

3.

If, however, the heir of any one

of the aforesaid has been under age and in wardship, let him

have his inheritance without relief and without fine when he

comes of age.

4.

The guardian of the land of an

heir who is thus under age, shall take from the land of the

heir nothing but reasonable produce, reasonable customs, and

reasonable services, and that without destruction or waste

of men or goods; and if we have committed the wardship of

the lands of any such minor to the sheriff, or to any other

who is responsible to us for its issues, and he has made

destruction or waster of what he holds in wardship, we will

take of him amends, and the land shall be committed to two

lawful and discreet men of that fee, who shall be

responsible for the issues to us or to him to whom we shall

assign them; and if we have given or sold the wardship of

any such land to anyone and he has therein made destruction

or waste, he shall lose that wardship, and it shall be

transferred to two lawful and discreet men of that fief, who

shall be responsible to us in like manner as aforesaid.

5.

The guardian, moreover, so long as

he has the wardship of the land, shall keep up the houses,

parks, fishponds, stanks, mills, and other things pertaining

to the land, out of the issues of the same land; and he

shall restore to the heir, when he has come to full age, all

his land, stocked with ploughs and wainage, according as the

season of husbandry shall require, and the issues of the

land can reasonable bear.

6.

Heirs shall be married without

disparagement, yet so that before the marriage takes place

the nearest in blood to that heir shall have notice.

7.

A widow, after the death of her

husband, shall forthwith and without difficulty have her

marriage portion and inheritance; nor shall she give

anything for her dower, or for her marriage portion, or for

the inheritance which her husband and she held on the day of

the death of that husband; and she may remain in the house

of her husband for forty days after his death, within which

time her dower shall be assigned to her.

8.

No widow shall be compelled to

marry, so long as she prefers to live without a husband;

provided always that she gives security not to marry without

our consent, if she holds of us, or without the consent of

the lord of whom she holds, if she holds of another.

9.

Neither we nor our bailiffs will

seize any land or rent for any debt, as long as the chattels

of the debtor are sufficient to repay the debt; nor shall

the sureties of the debtor be distrained so long as the

principal debtor is able to satisfy the debt; and if the

principal debtor shall fail to pay the debt, having nothing

wherewith to pay it, then the sureties shall answer for the

debt; and let them have the lands and rents of the debtor,

if they desire them, until they are indemnified for the debt

which they have paid for him, unless the principal debtor

can show proof that he is discharged thereof as against the

said sureties.

10.

If one who has borrowed from the

Jews any sum, great or small, die before that loan be

repaid, the debt shall not bear interest while the heir is

under age, of whomsoever he may hold; and if the debt fall

into our hands, we will not take anything except the

principal sum contained in the bond.

11.

And if anyone die indebted to the

Jews, his wife shall have her dower and pay nothing of that

debt; and if any children of the deceased are left under

age, necessaries shall be provided for them in keeping with

the holding of the deceased; and out of the residue the debt

shall be paid, reserving, however, service due to feudal

lords; in like manner let it be done touching debts due to

others than Jews.

12.

No scutage not aid shall be

imposed on our kingdom, unless by common counsel of our

kingdom, except for ransoming our person, for making our

eldest son a knight, and for once marrying our eldest

daughter; and for these there shall not be levied more than

a reasonable aid. In like manner it shall be done concerning

aids from the city of London.

13.

And the city of London shall have

all it ancient liberties and free customs, as well by land

as by water; furthermore, we decree and grant that all other

cities, boroughs, towns, and ports shall have all their

liberties and free customs.

14.

And for obtaining the common

counsel of the kingdom anent the assessing of an aid (except

in the three cases aforesaid) or of a scutage, we will cause

to be summoned the archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and

greater barons, severally by our letters; and we will

moveover cause to be summoned generally, through our

sheriffs and bailiffs, and others who hold of us in chief,

for a fixed date, namely, after the expiry of at least forty

days, and at a fixed place; and in all letters of such

summons we will specify the reason of the summons. And when

the summons has thus been made, the business shall proceed

on the day appointed, according to the counsel of such as

are present, although not all who were summoned have come.

15.

We will not for the future grant

to anyone license to take an aid from his own free tenants,

except to ransom his person, to make his eldest son a

knight, and once to marry his eldest daughter; and on each

of these occasions there shall be levied only a reasonable

aid.

16.

No one shall be distrained for

performance of greater service for a knight's fee, or for

any other free tenement, than is due therefrom.

17.

Common pleas shall not follow our

court, but shall be held in some fixed place.

18.

Inquests of novel disseisin, of

mort d'ancestor, and of darrein presentment shall not be

held elsewhere than in their own county courts, and that in

manner following; We, or, if we should be out of the realm,

our chief justiciar, will send two justiciaries through

every county four times a year, who shall alone with four

knights of the county chosen by the county, hold the said

assizes in the county court, on the day and in the place of

meeting of that court.

19.

And if any of the said assizes

cannot be taken on the day of the county court, let there

remain of the knights and freeholders, who were present at

the county court on that day, as many as may be required for

the efficient making of judgments, according as the business

be more or less.

20.

A freeman shall not be amerced for

a slight offense, except in accordance with the degree of

the offense; and for a grave offense he shall be amerced in

accordance with the gravity of the offense, yet saving

always his "contentment"; and a merchant in the same way,

saving his "merchandise"; and a villein shall be amerced in

the same way, saving his "wainage" if they have fallen into

our mercy: and none of the aforesaid amercements shall be

imposed except by the oath of honest men of the

neighborhood.

21.

Earls and barons shall not be

amerced except through their peers, and only in accordance

with the degree of the offense.

22.

A clerk shall not be amerced in

respect of his lay holding except after the manner of the

others aforesaid; further, he shall not be amerced in

accordance with the extent of his ecclesiastical benefice.

23.

No village or individual shall be

compelled to make bridges at river banks, except those who

from of old were legally bound to do so.

24.

No sheriff, constable, coroners,

or others of our bailiffs, shall hold pleas of our Crown.

25.

All counties, hundred, wapentakes,

and trithings (except our demesne manors) shall remain at

the old rents, and without any additional payment.

26.

If anyone holding of us a lay fief

shall die, and our sheriff or bailiff shall exhibit our

letters patent of summons for a debt which the deceased owed

us, it shall be lawful for our sheriff or bailiff to attach

and enroll the chattels of the deceased, found upon the lay

fief, to the value of that debt, at the sight of law worthy

men, provided always that nothing whatever be thence removed

until the debt which is evident shall be fully paid to us;

and the residue shall be left to the executors to fulfill

the will of the deceased; and if there be nothing due from

him to us, all the chattels shall go to the deceased, saving

to his wife and children their reasonable shares.

27.

If any freeman shall die

intestate, his chattels shall be distributed by the hands of

his nearest kinsfolk and friends, under supervision of the

Church, saving to every one the debts which the deceased

owed to him.

28.

No constable or other bailiff of

ours shall take corn or other provisions from anyone without

immediately tendering money therefor, unless he can have

postponement thereof by permission of the seller.

29.

No constable shall compel any

knight to give money in lieu of castle-guard, when he is

willing to perform it in his own person, or (if he himself

cannot do it from any reasonable cause) then by another

responsible man. Further, if we have led or sent him upon

military service, he shall be relieved from guard in

proportion to the time during which he has been on service

because of us.

30.

No sheriff or bailiff of ours, or

other person, shall take the horses or carts of any freeman

for transport duty, against the will of the said freeman.

31.

Neither we nor our bailiffs shall

take, for our castles or for any other work of ours, wood

which is not ours, against the will of the owner of that

wood.

32.

We will not retain beyond one year

and one day, the lands those who have been convicted of

felony, and the lands shall thereafter be handed over to the

lords of the fiefs.

33.

All kydells for the future shall

be removed altogether from Thames and Medway, and throughout

all England, except upon the seashore.

34.

The writ which is called praecipe

shall not for the future be issued to anyone, regarding any

tenement whereby a freeman may lose his court.

35.

Let there be one measure of wine

throughout our whole realm; and one measure of ale; and one

measure of corn, to wit, "the London quarter"; and one width

of cloth (whether dyed, or russet, or "halberget"), to wit,

two ells within the selvedges; of weights also let it be as

of measures.

36.

Nothing in future shall be given

or taken for a writ of inquisition of life or limbs, but

freely it shall be granted, and never denied.

37.

If anyone holds of us by fee-farm,

either by socage or by burage, or of any other land by

knight's service, we will not (by reason of that fee-farm,

socage, or burgage), have the wardship of the heir, or of

such land of his as if of the fief of that other; nor shall

we have wardship of that fee-farm, socage, or burgage,

unless such fee-farm owes knight's service. We will not by

reason of any small serjeancy which anyone may hold of us by

the service of rendering to us knives, arrows, or the like,

have wardship of his heir or of the land which he holds of

another lord by knight's service.

38.

No bailiff for the future shall,

upon his own unsupported complaint, put anyone to his "law",

without credible witnesses brought for this purposes.

39.

No freemen shall be taken or

imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed,

nor will we go upon him nor send upon him, except by the

lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

40.

To no one will we sell, to no one

will we refuse or delay, right or justice.

41.

All merchants shall have safe and

secure exit from England, and entry to England, with the

right to tarry there and to move about as well by land as by

water, for buying and selling by the ancient and right

customs, quit from all evil tolls, except (in time of war)

such merchants as are of the land at war with us. And if

such are found in our land at the beginning of the war, they

shall be detained, without injury to their bodies or goods,

until information be received by us, or by our chief

justiciar, how the merchants of our land found in the land

at war with us are treated; and if our men are safe there,

the others shall be safe in our land.

42.

It shall be lawful in future for

anyone (excepting always those imprisoned or outlawed in

accordance with the law of the kingdom, and natives of any

country at war with us, and merchants, who shall be treated

as if above provided) to leave our kingdom and to return,

safe and secure by land and water, except for a short period

in time of war, on grounds of public policy- reserving

always the allegiance due to us.

43.

If anyone holding of some escheat

(such as the honor of Wallingford, Nottingham, Boulogne,

Lancaster, or of other escheats which are in our hands and

are baronies) shall die, his heir shall give no other

relief, and perform no other service to us than he would

have done to the baron if that barony had been in the

baron's hand; and we shall hold it in the same manner in

which the baron held it.

44.

Men who dwell without the forest

need not henceforth come before our justiciaries of the

forest upon a general summons, unless they are in plea, or

sureties of one or more, who are attached for the forest.

45.

We will appoint as justices,

constables, sheriffs, or bailiffs only such as know the law

of the realm and mean to observe it well.

46.

All barons who have founded

abbeys, concerning which they hold charters from the kings

of England, or of which they have long continued possession,

shall have the wardship of them, when vacant, as they ought

to have.

47.

All forests that have been made

such in our time shall forthwith be disafforsted; and a

similar course shall be followed with regard to river banks

that have been placed "in defense" by us in our time.

48.

All evil customs connected with

forests and warrens, foresters and warreners, sheriffs and

their officers, river banks and their wardens, shall

immediately by inquired into in each county by twelve sworn

knights of the same county chosen by the honest men of the

same county, and shall, within forty days of the said

inquest, be utterly abolished, so as never to be restored,

provided always that we previously have intimation thereof,

or our justiciar, if we should not be in England.

49.

We will immediately restore all

hostages and charters delivered to us by Englishmen, as

sureties of the peace of faithful service.

50.

We will entirely remove from their

bailiwicks, the relations of Gerard of Athee (so that in

future they shall have no bailiwick in England); namely,

Engelard of Cigogne, Peter, Guy, and Andrew of Chanceaux,

Guy of Cigogne, Geoffrey of Martigny with his brothers,

Philip Mark with his brothers and his nephew Geoffrey, and

the whole brood of the same.

51.

As soon as peace is restored, we

will banish from the kingdom all foreign born knights,

crossbowmen, serjeants, and mercenary soldiers who have come

with horses and arms to the kingdom's hurt.

52.

If anyone has been dispossessed or

removed by us, without the legal judgment of his peers, from

his lands, castles, franchises, or from his right, we will

immediately restore them to him; and if a dispute arise over

this, then let it be decided by the five and twenty barons

of whom mention is made below in the clause for securing the

peace. Moreover, for all those possessions, from which

anyone has, without the lawful judgment of his peers, been

disseised or removed, by our father, King Henry, or by our

brother, King Richard, and which we retain in our hand (or

which as possessed by others, to whom we are bound to

warrant them) we shall have respite until the usual term of

crusaders; excepting those things about which a plea has

been raised, or an inquest made by our order, before our

taking of the cross; but as soon as we return from the

expedition, we will immediately grant full justice therein.

53.

We shall have, moreover, the same

respite and in the same manner in rendering justice

concerning the disafforestation or retention of those

forests which Henry our father and Richard our broter

afforested, and concerning the wardship of lands which are

of the fief of another (namely, such wardships as we have

hitherto had by reason of a fief which anyone held of us by

knight's service), and concerning abbeys founded on other

fiefs than our own, in which the lord of the fee claims to

have right; and when we have returned, or if we desist from

our expedition, we will immediately grant full justice to

all who complain of such things.

54.

No one shall be arrested or

imprisoned upon the appeal of a woman, for the death of any

other than her husband.

55.

All fines made with us unjustly

and against the law of the land, and all amercements,

imposed unjustly and against the law of the land, shall be

entirely remitted, or else it shall be done concerning them

according to the decision of the five and twenty barons whom

mention is made below in the clause for securing the pease,

or according to the judgment of the majority of the same,

along with the aforesaid Stephen, archbishop of Canterbury,

if he can be present, and such others as he may wish to

bring with him for this purpose, and if he cannot be present

the business shall nevertheless proceed without him,

provided always that if any one or more of the aforesaid

five and twenty barons are in a similar suit, they shall be

removed as far as concerns this particular judgment, others

being substituted in their places after having been selected

by the rest of the same five and twenty for this purpose

only, and after having been sworn.

56.

If we have disseised or removed

Welshmen from lands or liberties, or other things, without

the legal judgment of their peers in England or in Wales,

they shall be immediately restored to them; and if a dispute

arise over this, then let it be decided in the marches by

the judgment of their peers; for the tenements in England

according to the law of England, for tenements in Wales

according to the law of Wales, and for tenements in the

marches according to the law of the marches. Welshmen shall

do the same to us and ours.

57.

Further, for all those possessions

from which any Welshman has, without the lawful judgment of

his peers, been disseised or removed by King Henry our

father, or King Richard our brother, and which we retain in

our hand (or which are possessed by others, and which we

ought to warrant), we will have respite until the usual term

of crusaders; excepting those things about which a plea has

been raised or an inquest made by our order before we took

the cross; but as soon as we return (or if perchance we

desist from our expedition), we will immediately grant full

justice in accordance with the laws of the Welsh and in

relation to the foresaid regions.

58.

We will immediately give up the

son of Llywelyn and all the hostages of Wales, and the

charters delivered to us as security for the peace.

59.

We will do towards Alexander, king

of Scots, concerning the return of his sisters and his

hostages, and concerning his franchises, and his right, in

the same manner as we shall do towards our owher barons of

England, unless it ought to be otherwise according to the

charters which we hold from William his father, formerly

king of Scots; and this shall be according to the judgment

of his peers in our court.

60.

Moreover, all these aforesaid

customs and liberties, the observances of which we have

granted in our kingdom as far as pertains to us towards our

men, shall be observed b all of our kingdom, as well clergy

as laymen, as far as pertains to them towards their men.

61.

Since, moreover, for God and the

amendment of our kingdom and for the better allaying of the

quarrel that has arisen between us and our barons, we have

granted all these concessions, desirous that they should

enjoy them in complete and firm endurance forever, we give

and grant to them the underwritten security, namely, that

the barons choose five and twenty barons of the kingdom,

whomsoever they will, who shall be bound with all their

might, to observe and hold, and cause to be observed, the

peace and liberties we have granted and confirmed to them by

this our present Charter, so that if we, or our justiciar,

or our bailiffs or any one of our officers, shall in

anything be at fault towards anyone, or shall have broken

any one of the articles of this peace or of this security,

and the offense be notified to four barons of the foresaid

five and twenty, the said four barons shall repair to us (or

our justiciar, if we are out of the realm) and, laying the

transgression before us, petition to have that transgression

redressed without delay. And if we shall not have corrected

the transgression (or, in the event of our being out of the

realm, if our justiciar shall not have corrected it) within

forty days, reckoning from the time it has been intimated to

us (or to our justiciar, if we should be out of the realm),

the four barons aforesaid shall refer that matter to the

rest of the five and twenty barons, and those five and

twenty barons shall, together with the community of the

whole realm, distrain and distress us in all possible ways,

namely, by seizing our castles, lands, possessions, and in

any other way they can, until redress has been obtained as

they deem fit, saving harmless our own person, and the

persons of our queen and children; and when redress has been

obtained, they shall resume their old relations towards us.

And let whoever in the country desires it, swear to obey the

orders of the said five and twenty barons for the execution

of all the aforesaid matters, and along with them, to molest

us to the utmost of his power; and we publicly and freely

grant leave to everyone who wishes to swear, and we shall

never forbid anyone to swear. All those, moreover, in the

land who of themselves and of their own accord are unwilling

to swear to the twenty five to help them in constraining and

molesting us, we shall by our command compel the same to

swear to the effect foresaid. And if any one of the five and

twenty barons shall have died or departed from the land, or

be incapacitated in any other manner which would prevent the

foresaid provisions being carried out, those of the said

twenty five barons who are left shall choose another in his

place according to their own judgment, and he shall be sworn

in the same way as the others. Further, in all matters, the

execution of which is entrusted, to these twenty five

barons, if perchance these twenty five are present and

disagree about anything, or if some of them, after being

summoned, are unwilling or unable to be present, that which

the majority of those present ordain or command shall be

held as fixed and established, exactly as if the whole

twenty five had concurred in this; and the said twenty five

shall swear that they will faithfully observe all that is

aforesaid, and cause it to be observed with all their might.

And we shall procure nothing from anyone, directly or

indirectly, whereby any part of these concessions and

liberties might be revoked or diminished; and if any such

things has been procured, let it be void and null, and we

shall never use it personally or by another.

62.

And all the will, hatreds, and

bitterness that have arisen between us and our men, clergy

and lay, from the date of the quarrel, we have completely

remitted and pardoned to everyone. Moreover, all trespasses

occasioned by the said quarrel, from Easter in the sixteenth

year of our reign till the restoration of peace, we have

fully remitted to all, both clergy and laymen, and

completely forgiven, as far as pertains to us. And on this

head, we have caused to be made for them letters testimonial

patent of the lord Stephen, archbishop of Canterbury, of the

lord Henry, archbishop of Dublin, of the bishops aforesaid,

and of Master Pandulf as touching this security and the

concessions aforesaid.

63.

Wherefore we will and firmly order

that the English Church be free, and that the men in our

kingdom have and hold all the aforesaid liberties, rights,

and concessions, well and peaceably, freely and quietly,

fully and wholly, for themselves and their heirs, of us and

our heirs, in all respects and in all places forever, as is

aforesaid. An oath, moreover, has been taken, as well on our

part as on the art of the barons, that all these conditions

aforesaid shall be kept in good faith and without evil

intent.

Given under our hand - the

above named and many others being witnesses - in the meadow

which is called Runnymede, between Windsor and Staines, on the

fifteenth day of June, in the seventeenth year of our reign.

|

Participant list

Barons, Bishops and

Abbots who were party to Magna Carta.

Barons

Surety Barons for

the enforcement of Magna Carta (ancestors shown in

Green).

A surety is a person who agrees to be responsible for

the debt or obligation of another.

-

William

d'Albini, Lord of Belvoir Castle.

-

Roger Bigod,

Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk.

-

Hugh Bigod,

Heir to the Earldoms of Norfolk and Suffolk.

-

Henry de Bohun,

Earl of Hereford.

-

Richard de

Clare,

Earl of Hertford.

-

Gilbert de

Clare,

heir to the earldom of Hertford.

-

John FitzRobert,

Lord of Warkworth Castle.

-

Robert

Fitzwalter, Lord of Dunmow Castle.

-

William de

Fortibus, Earl of Albemarle.

-

William Hardell,

Mayor of the City of London.

-

William de

Huntingfield, Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk.

-

John de Lacie,

Lord of Pontefract Castle.

-

William de

Lanvallei, Lord of Standway Castle.

-

William Malet,

Sheriff of Somerset and Dorset.

-

Geoffrey de

Mandeville, Earl of Essex and Gloucester.

-

William

Marshall jr, heir to the earldom of Pembroke.

-

Roger de

Montbegon, Lord of Hornby Castle.

-

Richard de

Montfichet, Baron.

-

William de

Mowbray, Lord of Axholme Castle.

-

Richard de

Percy, Baron.

-

Saire/Saher de

Quincey, Earl of Winchester.

-

Robert de Roos,

Lord of Hamlake Castle.

-

Geoffrey de

Saye,

Baron.

-

Robert de Vere,

heir to the earldom of Oxford.

-

Eustace de Vesci, Lord of Alnwick Castle

|

Bishops

These bishops being

witnesses (mentioned by the King as his advisers in the

decision to sign the Charter):

-

Stephen

Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal of the

Holy Roman Church,

-

Henry,

Archbishop of Dublin

-

E. Bishop of

London,

-

J. Bishop of

Bath,

-

P. Bishop of

Winchester,

-

H. Bishop of

Lincoln,

-

R. Bishop of

Salisbury,

-

W. Bishop of

Rochester,

-

W. Bishop of

Worcester,

-

J. Bishop of

Ely,

-

H. Bishop of

Hereford,

-

R. Bishop of

Chichester,

-

W. Bishop of

Exeter.

Abbots

These abbots being

witnesses:

-

the Abbot of

St. Edmunds

-

the Abbot of

St. Albans

-

the Abbot of

Bello

-

the Abbot of

St. Augustines in Canterbury

-

the Abbot of

Evesham

-

the Abbot of

Westminster

-

the Abbot of

Peterborough

-

the Abbot of

Reading

-

the Abbot of

Abingdon

-

the Abbot of

Malmesbury Abbey

-

the Abbot of

Winchcomb

-

the Abbot of

Hyde

-

the Abbot of

Certesey

-

the Abbot of

Sherborne

-

the Abbot of

Cerne

-

the Abbot of

Abbotebir

-

the Abbot of

Middleton

-

the Abbot of

Selby

-

the Abbot of

Cirencester

Others

|

Our Magna Carta Surety Baron Ancestors

Roger Bigod

(c.

1150

–

1221),

was the son of

Hugh Bigod,

1st Earl of Norfolk and succeeded to the

earldom of

Norfolk in 1189, was confirmed in his earldom and

other honors by

Richard I,

for his claim had been disputed by his step-mother in the reign

of

Henry II.

King Richard also sent him to France as an ambassador in 1189.

Bigod is the name associated with Framlingham

Castle in Suffolk. It is an imposing structure. The outer walls

are forty-four feet high and eight feet thick. Thirteen towers

fifty-eight feet in height remain, along with a gateway and some

outworks. In early Roman times it was probably the site of the

fortified earthwork that sheltered Saint Edmund when he fled

from the Danes in 870, but we cannot be sure of the authenticity

of this tradition. The Danes seized the fort, but they lost it

in 921; it then remained a Crown possession, which passed into

the hands of William the Conqueror when he became King. In 1100

Henry I granted the Castle to Roger Bigod, and possibly Roger

was the one to erect the first masonry building. The ruins

indicate a 12th Century dating, though material from an older

building may very well have been used in the walls. Evidently

the Castle was completely rebuilt in 1170. It remained in the

Bigod family for some generations then passed into the hands of

the Mowbrays.

Earl of Norfolk is a title

which has been created several times in the Peerage of England.

Created in 1070, the first major dynasty to hold the title was

the 12th and 13th century Bigod family, and it then was later

held by the Mowbrays, who were also made Dukes of Norfolk. Due

to the Bigod's descent in the female line from William Marshal,

they inherited the hereditary office of Earl Marshal, still held

by the Dukes of Norfolk today. The present title was created in

1644 for Thomas Howard, 18th Earl of Arundel, the heir of the

Howard Dukedom of Norfolk which had been forfeit in 1572.

Arundel's grandson, the 20th Earl of Arundel and 3rd Earl of

Norfolk, was restored to the Dukedom as 5th Duke upon the

Restoration in 1660, and the title continues to be borne by the

Dukes of Norfolk.

He took part in the

negotiations for the release of Richard from prison, and after

the king's return to England became justiciar. Roger

Bigod was chosen to be one of the four Earls who carried the

silken canopy for the King, as Hugh Bigod had borne the Royal

scepter in the Royal procession.

Around Christmas

1181,

Roger married Ida de Tosney, a former mistress of King

Henry II,

and by her had a number of children, including:

-

Hugh

Bigod

-

William Bigod

-

Roger Bigod

-

John

Bigod

-

Ralph Bigod

-

Margaret Bigod

-

Mary

Bigod

-

da

Bigod

Roger Bigod was appointed in

1189 by King Richard one of the Ambassadors to King Philip of

France, to obtain aid for the recovery of the Holy Land. In 1191

he was keeper of Hereford Castle. He was chief judge in the

King's Court from 1195 to 1202. In 120() he was sent by King

John as one of his messengers to summon William the Lion, King

of Scotland, to do homage to him in the Parliament which was

held at Lincoln, and subsequently attended King John into

Poitou; but on his

return he was won over

to the opposition by the rebel Barons and became one of the

strongest advocates of the Charter of Liberty, for which he was

excommunicated by Pope Innocent III. He died before August

1221, having married as his first wife, Isabella daughter of

Hameline Plantagenet, who was descended from the Earls of

Warren.

Hugh Bigod

(c. 1182-1225)

was the eldest son of

Roger Bigod,

2nd Earl of Norfolk, and for a short time the 3rd

earl of

Norfolk. In 1215 he was one of the 25 sureties of

Magna Carta

of

King John.

He succeeded to his father’s estates (including

Framlingham

Castle) in

1221

but died in his early forties in 1225.

In late 1206 or early 1207,

Hugh was married to Maud Marshal (d.1248),

daughter of Sir

William

Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke. Together they had the

following children:

-

Roger

Bigod, 4th Earl of Norfolk, born c.1209.

-

Hugh Bigod,

justiciar of England.

-

Isabella Bigod

-

Ralph Bigod.

-

Simon Bigod died Bef. 1242(per Ancestral Roots of Certain

American Colonists Who Came to America Before 1700 by

Frederick Lewis Weis, Line 232-29)

Very

soon after Hugh's death, Maud married

William de

Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey.

Richard de Clare,

4th Earl of

Hertford (1162 – December 30, 1218) was the son of Roger

de Clare, 3rd Earl of Hertford and Maud de St. Hilary. More

commonly known as the Earl of Clare, he had the moiety of the

Giffard estates from his ancestor Rohese. He was present at the

coronation of King Richard I at Westminster, 3 Sep 1189, and

King John on 27 May 1199. He was also present at the homage of

King William of Scotland at Lincoln.

Hertford Castle of the

de Clares is one of two Castles: A 10th Century ruin or a 17th

Century structure. The older Castle retains a wall and part of a

Norman tower. The remainder of the building is a Jacobean

accretion made of brick and completely modernized.

He married (ca. 1172) Amice Fitz William, Countess of Gloucester

(ca. 1160-1220), second daughter of William Fitz Robert, 2nd

Earl of Gloucester, and Hawise de Beaumont. He sided with the

Barons against King John, even though he had previously sworn

peace with the King at Northampton, and his castle of Tonbridge

was taken. He played a leading part in the negotiations for

Magna Carta, being one of the twenty five Barons appointed as

guardians. On 9 Nov 1215, he was one of the commissioners on the

part of the Barons to negotiate the peace with the King. In

1215, his lands in counties Cambridge, Norfolk, Suffolk and

Essex were granted to Robert de Betun. He and his son were among

the Barons excommunicated by the Pope in 1215. Sometime before

1198 Earl Richard and his wife Amice were ordered to separate by

the Pope on grounds of consanguinity. They separated for a time

because of this order but apparently they reconciled their

marriage with the Pope later on.

Gilbert de Clare,

5th Earl of

Hertford (1180 – October 25, 1230) was the son of Richard de

Clare, 4th Earl of Hertford, from whom he inherited the Clare

estates, from his mother, Amice Fitz Robert, the estates of

Gloucester and the honor of St. Hilary, and from Rohese, an

ancestor, the moiety of the Giffard estates. In June 1202, he

was entrusted with the lands of Harfleur and Montrevillers.

Gilbert de Clare built a

Castle at Caerdigan, Pembrokeshire, Wales. A marriage brought it

into the hands of William Marshall, who soon controlled the

strongest castles on the peninsula. The keep has been

transformed into a modern house. Of all the castles that finally

came into William Marshall's possession, this was the most

important to the area. Scholars believe there is evidence that

it was originally built of wood.

In 1215

Gilbert and his father were two of the barons made Magna Carta

sureties and championed Louis "le Dauphin" of France in the

First Barons' War, fighting at Lincoln under the baronial

banner. He was taken prisoner in 1217 by William Marshal, whose

daughter Isabella he later married. In 1223 he accompanied his

brother-in-law, Earl Marshal in an expedition into Wales. In

1225 he was present at the confirmation of the Magna Carta by

Henry III. In 1228 he led an army against the Welsh, capturing

Morgan Gam, who was released the next year. He then joined in an

expedition to Brittany, but died on his way back to Penrose in

that duchy. His body was conveyed home by way of Plymouth and

Cranbourgh to Tewkesbury. His widow Isabel later married Richard

Plantagenet, Earl of Cornwall & King of the Romans.

John FitzRobert married Ada

Baliol and in her right became lord of Barnard Castle whose

founder was Barnard Baliol. The Castle is now a scanty ruin, but

the remaining walls stand high on a cliff scarped, so that wall

and bank are one, dropping down to the River Tees. The Castle

looms over the town, and may be approached through a gate in the

yard of the King's Head Inn.

The date of the Castle's

founding is between 1112 and 1132. The keep, known as Baliol's

Tower, stands fifty feet high and served as a background for Sir

Walter Scott's Rokeby. The surrounding property extends over six

acres.

FitzRobert was also lord of the

handsome Warkworth Castle in the border country of

Northumberland. It is an excellently preserved fortress built,

at the earliest, in the 12th Century. It is situated near the

mouth of the Coquet River. One approaches it from a double

arched bridge and finds that it is bounded on three sides by

water. The walls, gateway and Great Hall are intact, as are the

Lion Tower of the 13th Century and the 14th Century keep. Robert

FitzRichard probably added to it in Henry II's

reign. It became the property of the Percy

family in the reign of Edward III, and is now held by the Dukes

of Northumberland.

When the Barons met at

Saint Edmondsbury, John FitzRobert was still loyal to King John

and was, with John Marshall, joint governor of the Castles of

Norwich and Oxford. Subsequently he joined the insurrection, and

took such a prominent part that his lands were seized by the

King. He returned allegiance in the next reign, his Castles and

vast estates were returned to him, and he was constituted High

Sheriff of co. Northumberland and governor of

New-Castle-upon-Tyne. He died in 1240, the same year as his

father. The monk, Matthew Paris, records: "In this year died

John FitzRobert, a man of noble birth, and one of the chief

Barons of the Northern provinces of England."

John de Lacie

was born 1192, seventh Baron of Halton Castle and hereditary

constable of Chester. The Lacie strongholds on the Welsh border

are Beeston, Chester and Halton Castles. Beeston is now a

crumbling ruin. It is hard even to identify the keep, but it

could be the large wall tower East of the gate house. The Castle

is perched on a height bounded on three sides by sheer drops,

and a steep slope on the fourth. Its strength as a defense lay

in its inaccessibility. There are two baileys, the innermost on

a summit and the other situated on the sloping ground. The inner

bailey was guarded on the approachable side by a gate house, two

wall towers and a ditch thirty-five feet wide and thirty feet

deep, which cut across the promontory. It is important to note

that the artificial ravine was fashioned two hundred fifty years

before blasting was known. The date of founding was in the 13th

Century, and it was founded by Randolph de Blondevill, Earl of

Chester.

Chester was the last

City to yield to William the Conqueror, and the surrender came

in 1070. Once the Normans had the Castle, William's nephew, Hugh

Lupus, Palatine Earl of Chester, was appointed as head of the

border patrol.

Chester Castle was

originally built by the first Norman Earl of Chester, and now

consists of modern buildings, the assize-court, jail and

barracks. The one remaining Norman relic is "Julius Caesar's

Tower," standing by the River. It is a square tower which has

been used as a powder magazine, but is scarcely recognizable as

a Norman building, because it has been recently re-cased in red

stone. With the exception of this tower, another of the round

style, and adjacent buildings in the upper ward, the Castle was

dismantled at the end of the 18th Century. From Julius Caesar's

Tower one can see the ruins of Beeston Castle, which met a like

fate in 1646. Of Halton Castle nothing is left.

Lincoln was the fourth

City of the Realm when the Normans invaded, and it seemed to

William to be a logical site for a castle. The Domesday Book

states that one hundred sixty-six houses were torn down to make

way for it. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle held that on his return to

York in 1068, William erected the Castle on the site of a Roman

fort. Since the land was rather flat, a great bank was built up

around it. There are two motes, the larger one crowned by a

polygonal shell wall, which may have been built by Ralph de

Gernon's widow. In 1140 King Stephen captured the Castle and, in

1216, the Surety Barons had charge of it.

De Lacie was one of the

earliest Barons to take up arms at the time of Magna Charta. He

was also appointed to see that the new statutes were properly

carried into effect and observed in the counties of York and

Nottingham. He was excommunicated by the Pope. Upon the

accession of King Henry III, he joined a party of noblemen and

made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, rendering valuable service

at the Siege of Damietta.

In 1232 Lacie was made

Earl of Lincoln and, in 1240, governor of Chester and Beeston

Castles. He died 22 July 1240, and was buried in the Cistercian

Abbey of Stanlaw in co. Chester. The monk, Matthew Paris,

records: "On the 22d day of July, in this year (1240), which was

St. Magdalen's Day, John, Earl of Lincoln, after suffering from

a long illness went the way of all flesh." His first wife was

Alice, daughter of Gilbert 'd’Aquila, but by her he had no

issue. She died in 1215 and he married second, after his marked

gallantry at the Siege of Damietta, Margaret, only daughter and

heiress of Robert de Quincey, a fellow Crusader, who died in the

Holy Land, eldest son of Saire de Quincey, the Surety. They had

three children; Lady Margaret survived him and married second

Walter Marshall, Earl of Pembroke.

William Malet was

mentioned as a minor in the year 1194, in connection with an

expedition made that year into Normandy. His principal estate

was Curry-Malet. From 1210 to 1214 he was sheriff of counties

Somerset and Dorset. He then joined the Barons against King John

and became one of the Sureties. He had lands in four counties

which were confiscated and given to his son-in-law, Hugh de

Vivonia, Thomas Basset, and to his father-in-law, and Malet was

excommunicated by the Pope in 1216. He was also fined 2,000

marks, but the sum was not paid until after his death, and at

that time 1,000 marks were remitted, being found due to him for

military service to King John in Poitou. It is interesting to

note that there were five contemporary relatives named Malet,

all of whom held lands in England or in Jersey. William Malet

died about 1217, having married Mabel, called also Alice and

Aliva, daughter of Thomas Basset of Headington. Nothing now

remains of Malet's estate of Curry-Malet.

Geoffrey de Saye was

in arms with the other Barons against the King, and consequently

his extensive lands and possessions in ten counties were seized.

These were given to Peter de Crohim. Six of the counties we can

name: Northampton, Cambridge, Essex, Norfolk, Suffolk and

Lincoln, but we cannot be sure of what Castles in those areas

were Geoffrey's, or which other four counties he could claim.

While William d'Albini

and his companions were holding Rochester Castle, they had been

assured that other Baronial leaders would relieve them if the

Castle were to be besieged by King John. Such a rescue would not

have been easy unless the Royal guards were lax in watching the

bridge over the Medway. If this bridge were under guard, a march

to Rochester from London along the Dover Road would prove

impossible, the company then being forced to detour and approach

Rochester from Maidstone. Nevertheless, on 26 October, they

moved in as far as Dover, where they soon heard that the King

was on his way to meet them. They promptly returned to London,

leaving the Rochester garrison to do the best it could.

Perhaps the march on

Rochester was a sop to the Barons' consciences. Had it been a

serious move, it would have been an extraordinarily foolish one.

The only other attempt to save Rochester was negotiatory. On 9

November King John issued letters of conduct for Richard de

Clare, Robert FitzWalter, Geoffrey de Saye and the Mayor of

London, to confer with the Royal emissaries: Peter de Roches,

Hubert de Burgh and the Earls of Arundel and Warren. There is no

certainty that these men ever met. If indeed they did, nothing

came of it. We suspect that the meeting was originally planned

with the hope that a proposal would be accepted, and it is not

unlikely that the proposal would have been a willingness to

surrender Rochester Castle to the King if the garrison could go

free, but no such move resulted. Yet despite the futility of the

meeting, at least we see Geoffrey de Saye connected, if lightly,

with Rochester Castle. And this is the only Castle with which we

are able to link his name.

Geoffrey de Saye returned to

the Royalist party when the civil war was over, and sided with

King Henry III, thereby regaining his lost lands after the

expulsion of the Dauphin. He died 24 October 1230 leaving a son,

William, as his heir, by Alice, daughter of William de Cheney.

King John "Lackland" I

was born in

Beaumont Palace, Oxford, England December 24, 1167. King

of England and Ireland (1199-1216) of the house of Plantagenet,

the youngest son of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of

Aquitaine. He was often called John Lackland because Henry

provided his elder sons with dominions but granted none to

John. When Richard I, one of John's older brothers became king

in 1189, he conferred upon John earldoms which comprised nearly

a third of England. Nevertheless John attempted to seize the

crown while Richard was being held for ransom in Austria

(1192-94), where he had been imprisoned on his way back to

England from Palestine after the Third Crusade. John did not

succeed, and Richard on his return to England pardoned him and

later reputedly designated him as his successor. After

Richard's death in 1199, the legitimate heir was Arthur, son of

Geoffrey, another older brother of John; but John had himself

crowned king at Westminster in 1199, and fought in France

against Arthur and the French under King Philip II, who

supported Arthur's claim. John succeeded in capturing Arthur

and, according to tradition, had him put to death at Rouen; but

in subsequent warfare he lost to Philip the duchies of Normandy,

Touraine, Maine, Anjou, and Poitou, which John had inherited

when he became king.

John was a

cruel and tyrannical monarch, and his disregard of the rights or

claims oaf others brought him into violent conflict in domestic

affairs with the papacy, and later with the barons of England.

In 1206 John refused to accept as archbishop of Canterbury the

prelate favored by Pope Innocent III and in 1208 the pope

punished John by issuing an interdict against England. In

retaliation John confiscated the property of the clergy,

whereupon the pope deposed John and commissioned Philip of

France to carry out the execution of the deposition. John, who

was hated by his subjects, found himself without support to

fight the French king, and in 1213 to forestall a French

invasion, he yielded to the pope, agreeing to hold England as a

fief from the papacy. Although the pope no longer favored

invasion, Philip set out for England, but his fleet was defeated

by the English fleet of the Belgium coast and he did not reach

England. John in turn invaded France, but was crushingly

defeated in 1214 at Bouvines, near Lille.

The

English barons, who had long been rebellious because of John's

abuses in the administration of justice, saw in John's defeat an

opportunity to end his tyranny. On his return to England they

drew up a petition demanding the issuance by him of a charter

modeled on the charter granted by Henry I which would secure to

the subjects of the kings of England their political and

personal rights. John refused to issue such a charter and

prepared to fight the barons. Once again he found himself

without support, and when the barons raised an army and marched

on London, he submitted. On June 15, 1215, at Runnymede he

unwillingly signed the famous Magna Charta. He soon prevailed on

the pope to issue a bull annulling the charter, raised an army

of foreign mercenaries, and began a war with the barons. John

died before the war was decided. He was succeeded by his son

Henry, who ruled as Henry III.

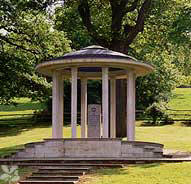

Runnymede

Runnymede or Runnimede

(rŭn'ĭmēd)

is a water meadow, in Egham, Surrey, S England, on the south

bank of the Thames River, W of London. It was either on this

meadow or on nearby Charter Island, King John signed the Magna

Carta in 1215.

The water-meadow at

Runnymede is the most likely location at which, in 1215, King

John sealed the Magna Carta, and the charter itself indicates

Runnymede by name. It has been disputed whether the ceremony

took place actually in the meadow, or on Magna Carta Island, a

small (and now private) island in the Thames adjacent to the

meadow, or at Ankerwycke, an

ancient place adjoining Magna Carta Island on the far bank.

Although the latter two locations are now in Berkshire, they may

have been considered part of Runnymede at the time.

Twenty miles

southwest of London, Runnymede Meadow, with adjoining lands

totaling 182 acres, was presented to the National Trust by the

first Lady Fairhaven and her two sons in memory of Urban Hanlon

Broughton in 1929. The memorial to Broughton consists of the

kiosks, piers and lodges ('The Fairhaven Lodges') at the Windsor

end designed by Edwin Lutyens.

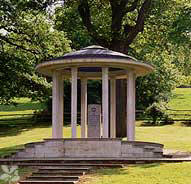

The Magna Carta Memorial at

Runnymede

Standing at the foot of the

Cooper's Hill Slopes is a memorial to the Magna Carta in the

form of a domed classical temple containing a pillar of English

granite on which is inscribed: 'To commemorate Magna Carta,

symbol of Freedom Under Law.' This was built by the American Bar

Association on land leased by the Magna Carta Trust. It was paid

for by voluntary contributions of some 9,000 American lawyers.

The memorial was designed by Sir Edward Maufe R.A. and unveiled

on 18 July 1957 at a ceremony attended by American and English

lawyers.

|