|

PRINT Version

of this article

Link to

The American

College of Heraldry

Link to

Burkes Peerage and

Gentry International Register of Arms

Link to

College of Arms

(UK)

Back to

|

Heraldry

in its most general sense encompasses all matters relating to the

duties and responsibilities of

officers of arms.

To most, though, heraldry is the practice of designing, displaying,

describing and recording

coats of arms

and

badges. The

origins of heraldry lie in the need to distinguish participants in

combat when their faces were hidden by iron and steel

helmets.

Origins and

History

At

the time of the

Norman Conquest

of England, modern heraldry had not yet been developed. The beginnings

of modern heraldic structure were in place, but would not become

standard until the middle of the twelfth century. By the early

thirteenth Century, coats of arms were being inherited by the children

of

armigers.

In Britain the practice of using marks of

cadency

arose to distinguish one son from another, and was institutionalized and

standardized by the

John Writhe

in the fifteenth century.

In the late

Middle Ages

and the

Renaissance,

heraldry became a highly developed discipline, regulated by professional

officers of arms. As its use in jousts became obsolete coats of arms

remained popular for visually identifying a person in other

ways—impressed in

sealing wax

on documents, carved on family tombs, and flown as a banner on country

homes.

From the

beginning of heraldry, coats of arms have been executed in a wide

variety of media, including on paper, painted wood,

embroidery,

enamel,

stonework,

stained glass,

and computerized media. For the purpose of quick identification in all

of these, heraldry distinguishes only seven basic

colors and

makes no fine distinctions in the precise size or placement of

charges on

the field. Coats of arms and their accessories are described in a

concise

jargon

called

blazon.

This technical description of a coat of arms is the standard that must

be adhered to no matter what artistic interpretations may be made in a

particular depiction of the arm

The idea that

each element of a coat of arms has some specific meaning is unfounded.

Though the original armiger may have placed particular meaning on a

charge, these meanings are not necessarily retained from generation to

generation. Unless the arms incorporate an obvious pun on the bearer's

name, it is difficult to find meaning.

The development

of

firearms

made

plate armor

obsolete and heraldry became detached from its original function. This

brought about the development of "paper heraldry" that only existed in

paintings. Designs and shields became more elaborate at the expense of

clarity. The 20th century's taste for stark iconic emblems made the

simple styles of early heraldry fashionable again.

The Rules of Heraldry

Shield and Lozenge

The

focus of modern heraldry is the armorial achievement, or

coat of arms.

The central element of a coat of arms is the

shield. In

general the shape of shield employed in a coat of arms is irrelevant.

The fashion for shield shapes employed in heraldic art has generally

evolved over the centuries. There are times when a particular shield

shape is specified in a blazon.

Traditionally,

as women did not go to war, they did not use a shield. Instead their

coats of arms were shown on a

lozenge—a

rhombus

standing on one of its acute corners. This continues to hold true in

much of the world, though some heraldic authorities make exceptions. In

Canada the restriction against women bearing arms on a shield has been

completely eliminated. Noncombatant

clergy have

also made use of the lozenge as well as the cartouche—an

oval-shaped

vehicle for their display.

Tinctures are the colors used in heraldry. Since heraldry is

essentially a system of identification, the most important

convention of heraldry is the

rule of

tincture. To provide for contrast and visibility

metals—generally lighter tinctures—must never be placed on

metals and colors—generally darker tinctures—must never be

placed on colors. There are instances where this cannot be help,

such as where a

charge

overlays a partition of the field. Like any rule, this admits

exceptions, the most famous being the arms chosen by

Godfrey of

Bouillon when he was made

King of

Jerusalem.

The

names used in English blazon for the tinctures come mainly from

French

and include

Or

(gold),

Argent

(white),

Azure

(blue),

Gules

(red),

Sable

(black),

Vert

(green), and

Purpure

(purple). A number of other colors are occasionally found,

typically for special purposes.

Besides

tinctures, certain patterns called

furs

can appear in a coat of arms. The two common furs are

ermine

and

vair.

Ermine represents the winter coat of the

stoat,

which is white with a black tail. Vair represents a kind of

squirrel with a blue-gray back and white belly sewn together it

forms a pattern of alternating blue and white shapes.

Heraldic charges can also be displayed in their natural colors.

Many natural items such as plants and animals are described as

proper in this case. Proper charges are very frequent as crests

and supporters. It is considered bad form to use proper as a

method of circumventing the tincture convention.

Division of the Fields

The

field

of a

shield

in heraldry can be divided into more than one

tincture,

as can the various

heraldic

charges. Many coats of arms consist simply of a

division of the field into two contrasting tinctures. Since

these are considered divisions of a shield the

rule of

tincture can be ignored. For example, a shield

divided azure and gules would be perfectly acceptable. A line of

partition may be straight or it may be varied. The variations of

partition lines can be wavy, indented, embattled, engrailed, or

made into myriad other forms.

Ordinaries

In the

early days of heraldry, very simple bold rectilinear shapes were

painted on shields. These could be easily recognized at a long

distance and could also be easily remembered. They therefore

served the main purpose of heraldry—identification. As more

complicated shields came into use, these bold shapes were set

apart in a separate class as the "honorable ordinaries." They

act as charges and are always written first in

blazon.

Unless otherwise specified they extend to the edges of the

field. Though ordinaries are not easily defined, they are

generally described as including the

cross,

the

fess,

the

pale,

the

bend,

the

chevron,

the

saltire,

and the

pall.

There is also a

separate class of charges called sub-ordinaries which are of geometrical

shape subordinate to the ordinary. According to Friar, they are

distinguished by their order in blazon. The sub-ordinaries include the

inescutcheon,

the

orle, the

tressure,

the double tressure, the

bordure,

the

chief, the

canton, the

label, and

flaunches.

Ordinaries may

appear in parallel series, in which case English blazon gives them

different names such as pallets, bars, bendlets, and chevronels. French

blazon makes no such distinction between these diminutives and the

ordinaries when borne singly. Unless otherwise specified an ordinary is

drawn with straight lines, but each may be indented, embattled, wavy,

engrailed, or otherwise have their lines varied.

Charges

A

charge is any object or figure placed on a heraldic shield or on any

other object of in an

armorial composition.

Any object found in nature or technology may appear as a heraldic charge

in armory. Charges can be animals, objects, or geometric shapes. Apart

from the ordinaries, the most frequent charges are the

cross—with

its hundreds of variations—and the

lion and

eagle.

Other common animals are

fish,

martlets,

griffins,

boars, and

stags.

Dragons,

unicorns,

and more exotic monsters appear as charges but also as

supporters.

Animals are

found in various stereotyped positions or attitudes.

Quadrupeds

can often be found rampant—standing on the left hind foot. Another

frequent position is passant, or walking, like the lions of the

Coat of Arms of

England. Eagles are almost always shown with their wings

spread, or displayed.

In

English heraldry

the

crescent,

mullet,

martlet,

annulet,

fleur-de-lis,

and

rose may be

added to a shield to distinguish

cadet

branches of a family from the senior line. These cadency marks are

usually shown smaller than normal charges, but it still does not follow

that a shield containing such a charge belongs to a cadet branch. All of

these charges occur frequently in basic undifferenced coats of arms.

Marshalling

Marshalling is the art of correctly arranging armorial bearings. Two or

more coats of arms are often combined in one shield to express

inheritance, claims to property, or the occupation of an office.

Marshalling can be done in a number of ways, but the principal modes of

include impalement and dimidiation. This involves using one shield with

the arms of two families or corporations on either half. Another method

is called quartering, in which the shield is divided into quadrants. One

might also place a small inescutcheon of a coat of arms on the main

shield.

When more than

four coats are to be marshalled, the principle of quartering may be

extended to two rows of three (quarterly of six) and even further. A few

lineages have accumulated hundreds of quarters, though such a number is

usually displayed only in documentary contexts. Some traditions have a

strong resistance to allowing more than four quarters, and resort

instead to sub-quartering.

Helm and Crest

In

English the word "crest" is commonly used to refer to a coat of arms—an

entire heraldic achievement. The correct use of the heraldic term

crest

refers to just one component of a complete achievement. The crest rests

on top of a

helmet

which itself rests on the most important part of the achievement—the

shield. The crest is usually found on a

wreath of

twisted cloth and sometimes within a coronet. The modern crest has

evolved from the three-dimensional figure placed on the top of the

mounted knights' helms as a further means of identification. In most

heraldic traditions a woman does not display a crest, though this

tradition is being relaxed in some heraldic jurisdictions.

When the helm

and crest are shown, they are usually accompanied by a

mantling.

This was originally a cloth worn over the back of the helmet as partial

protection against heating by sunlight. Today it takes the form of a

stylized cloak or hanging from the helmet. Typically in British

heraldry, the outer surface of the mantling is of principal color in the

shield and the inner surface is of the principal metal. The mantling is

conventionally depicted with a ragged edge, as if damaged in combat.

Clergy often

refrain from displaying a helm or crest in their

heraldic achievements.

Members of the

Roman Catholic

clergy may display appropriate headwear. This takes the form of a

galero with

the colors and tassels denoting rank. In the

Anglican

tradition, clergy members may pass crests on to their offspring, but

rarely display them on their own shields.

Mottoes

An

armorial

motto is a

phrase or collection of words intended to describe the motivation or

intention of the armigerous person or corporation. This can also form a

pun on the family name as in the

Neville

motto "Ne vile velis." Mottos are generally changed at will and do not

make up an integral part of the armorial achievement. Mottoes can

typically be found on a scroll under the shield. In

Scottish heraldry

where the motto is granted as part of the blazon, it is usually shown on

a scroll above the crest. A motto may be in any language.

Supporters and

Other Insignia

Supporters

are human or animal figures placed on either side of a coat of arms as

though supporting it. In many traditions, these have acquired strict

guidelines for use by certain social classes. On the European continent,

there are often less restrictions on the use of supporters. In Britain

only

peers of

the realm, senior members of orders of knighthood, and some corporate

bodies are granted supporters. Often these can have local significance

or a historical link to the armiger.

If the armiger

has the title of

baron,

hereditary

knight, or

higher, he or she may display a coronet of rank above the shield. In

Britain this is usually below the helmet, though it is often above the

crest in Continental heraldry.

Another

addition that can be made to a coat of arms is the insignia of an order

of knighthood. This is usually represented by a collar or similar band

surrounding the shield. When the arms of a knight and his wife are shown

in one achievement, the insignia of knighthood surround the husband's

arms only, and the wife's arms are customarily surrounded by a

meaningless ornamental garland of leaves for visual balance.

Modern Heraldry

Heraldry continues to flourish today in the modern day. Institutions,

companies, and members of the public may obtain officially recognized

coats of arms from governmental heraldic authorities. However, many

users of modern heraldic designs do not register with heraldic

authorities, and some designers do not follow the rules of heraldic

design at all.

In Scotland the

control of heraldry is fully legal and the

Lord Lyon King of Arms

retains powers—including imprisonment, fines, and defacement of

illegitimate arms. His office has no equivalent in England and is closer

to that of the

Earl Marshal

than that of

Garter Principal King

of Arms.

The

Heineman Arms

The

Heineman Armorial Bearings are registered to Wilhelm August Heineman,

late of Keokuk, Lee County, Iowa; the son of John Henry Heineman and

Bertha Ann Heineman, nee Burger; recognized 16 January 1999 and entered

in the Heraldic Register (American College of Heraldry) under Number

1778.

The

blazon for the Heineman Armorial Bearings is as follows:

Per fess Gules and Azure

a barrulet Argent, over-all an eagle displayed wings inverted Or,

charged on the breast with a fleur-de-lis Azure. Above the Shield is

placed a Helmet with a Mantling Gules doubled Or, and on a Wreath Or and

Gules is set for Crest, a castle with two towers Argent the port

occupied by a cross throughout Gules, and issuing there above three

trees in Autumn tinctures Proper, and in an Escrol below the Shield this

Motto: Leadership Through Service.

The Shield

A "fess"

is associated with the military girdle and belt of the ancients and

their nobility. The red, white, and blue shield colors were chosen to

signify American service. The eagle has a number of meanings. The

surname Jensen is a variant of the "son of Jens" or the "son of John."

Usually this has an ancient allusion to respect for St. John, who is

represented by the eagle in ancient and modern religious iconography.

The eagle with turned-down wings alludes to Germanic ancestry. The

fleur-de-lis on a golden background (a reversal of the ancient French

flag colors) alludes to Wilhelm's military service for the United States

in France as part of the Allied Forces during WWI. The fleur-de-lis is

representative of the Crum family origins. The fleur-de-lis is an

adaptation of the lily, generally recognized as one of the most highly

regarded charges with those of royalty and nobility. The three leaves

of the fleur-de-lis represent courage, faith, and wisdom.

The Helm

The

proper helmet of a gentleman's coat of arms is the "tilting" helm.

The Crest

A wreath

or torce is common in

early arms. The castle in the crest alludes to the Burger (meaning

dweller in a castle or town). Growing from the castle is a grove of

trees, alluding to the Heineman name meaning a man who lives in or

protects a grove or forest. The trees are in Autumn colors to keep from

clashing with the other tinctures. The cross on the castle port is of

Germanic design referring to the Christian faith.

The Motto

The motto

represents the family's dedication to service organizations and their

leadership roles.

Rightful Bearers of the Arms

The bearer of

a coat of arms is called the Arminger (Wilhelm August Heineman) and the

arms are passed to the male heirs in direct lineage. The following

individuals have rightful use of these arms: Lucille Ann Dodson, Peter

Edward Heineman, Sharen Lee Heineman, Bim August Heineman, Peter Lea

Heineman, Chad August Heineman.

Ancestral Arms

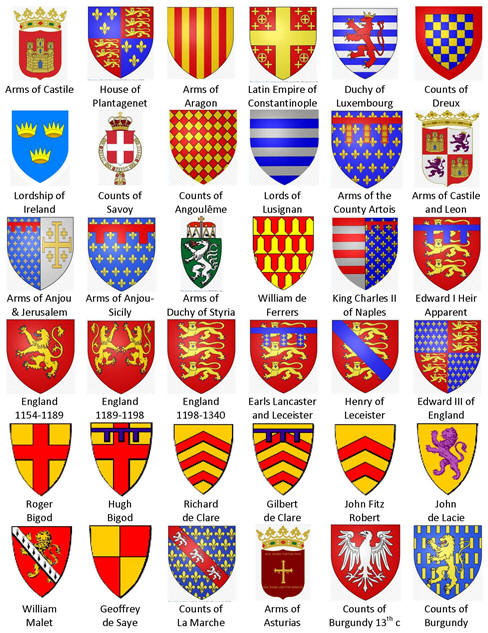

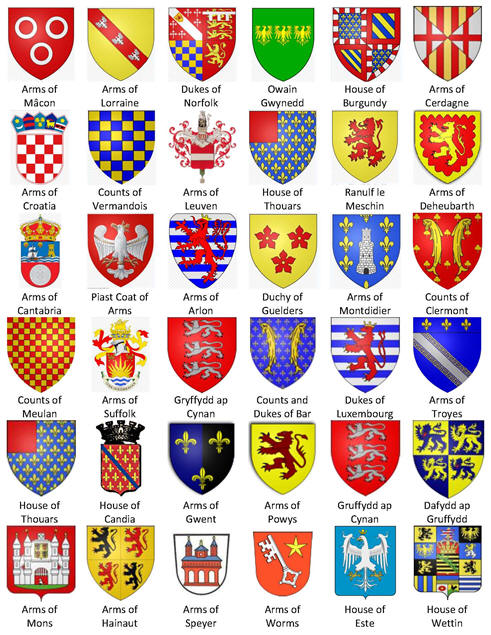

The

following are representative of some of the coat of arms used by

ancestors of the Heineman family.

|