| This Week’s Topic… | |||

Best viewed in

|

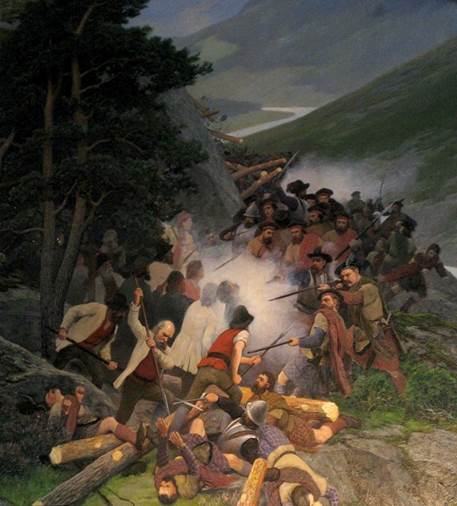

The Battle of Kringen Between 1618 and 1648, about 50,000 Scots fought as mercenaries on the continent, largely during the Thirty Years' War. Of these, 18 became generals. One small band spent less than a week on foreign soil, but yet managed to pass into folklore and relight the flame of Norwegian patriotism that had almost flickered out during the nation's '400-year night', when it was united with Denmark. In 1612, Denmark was fighting Sweden. Kalmar in southern Norway was the battleground. Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, had already recruited more than 1,000 Scots and wished to bring over 1,000 more. But King James was married to Anne of Denmark and did not want his subjects fighting against his brother-in-law, so he forbade this. Nevertheless, 300 men managed to take to their ships before the authorities could put a stop to them. Many had been forcibly enlisted in Caithness and in the rush they were ill-armed and were told they would collect weapons when they reached Sweden. The direct sea route was blocked by Danish warships so, under the command of Lt-Col Alexander Ramsay, they penetrated deep into Romsdal fjord in western Norway before landing, on 20 August, with the intention of marching south to join their compatriots. The countryside looked like the Highlands of Scotland on steroids. The hills were twice as high and the glens twice as steep, with even less cultivation and fewer people. But Scots mercenaries had travelled this route through the district of Gudbrandsdalen before. The locals were under Danish rule and thus enemies but they were peaceful and did not interfere with travelers such as themselves. The year before, the Danish king ordered the recruitment of 8,000 Norwegians. No more than 2,000 could be found. They disobeyed orders and soon most deserted, leaving only 200 men. Nonetheless the Scots were careful to do nothing to provoke them, bar borrow the occasional citizen as a guide. People evacuated their farms on the column's approach, but left tables laden with food, the pact being that the Scots would not plunder or commit the atrocities common at the time. However, the Scots were unaware that the young men in the region had been conscripted into the Danish army and 300 had recently been massacred by the Swedes. Furthermore, there were rumors of depredations being carried out by Dutch mercenaries further south. From the hilltops, local peasants shadowed the march, lit beacons and sent ahead warnings of its progress. On 23 August, the local magistrate marched into the church at Dovre during the service, pounded his battle axe three times on the floor and announced that they must summon able-bodied men to defend their communities because the enemy was at hand. In a short time, 500 peasants had gathered and been armed with swords, scythes and assorted firearms. The Scots were oblivious to the threat. They were making good time, had scouts with hounds ranging ahead of them and, if the animals kept disappearing, it was no great surprise because the terrain was extremely rough and there must be plenty of distractions for them. In the evening there was always a handy farmstead at which to camp, often with a bullock left tethered to a fence for their supper. They had their bagpipes to keep themselves amused and frosts were still rare. Wednesday 26 August, 150 miles into their journey, dawned a fine day. The Scots set off, straggling along a narrow path across the steep and rocky hillside about 100 feet above a river. Their piper was playing a march and their drums tapped a rhythm to which they stumbled to keep step. They rounded a bluff and here there was a straight course until the next promontory. The river was studded by substantial islands, on one of which a peasant was ambling along on a horse. Then from the top of a hillside that soared to the sky on the opposite bank of the river, they heard the haunting notes of a cattle horn playing a melody. It kept their attention away from the slope above them. The horseman abruptly reversed his course. It was a signal. A shot rang out and Captain George Sinclair, the second-in-command, fell dead with a bullet – a silver bullet in case he had been protected by charms – in his heart.

|

||