| This Week’s Topic… | |

Best viewed in

|

Canntaireachd Canntaireachd (Scottish Gaelic: literally, "chanting") is the ancient Scottish Highland method of noting classical pipe music or Ceol Mor by a combination of definite syllables, by which means the various tunes could be more easily recollected by the learner, and could be more easily transmitted orally. Nowadays, however, pipers tend to use standard musical staff notation to read and write various tunes, and anyone attempting to read this particular system needs some familiarity with Scottish Gaelic phonetics. It does still linger on in one or two places however. In general, the vowels represent the notes, and consonants the embellishments, but this is not always the case, and the system is actually extremely complex, and was not fully standardized. Although a similar system of chant may have been in use since the sixteenth century, there is no evidence of it being written down before the 1790s. The piper to the Earl of Breadalbane, Colin Campbell, recorded 168 piobaireachd in the manner most obvious to him. Simply transcribed to paper, however, he found his teachers’ canntaireachd to be fairly unintelligible.

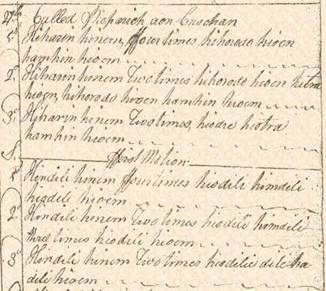

Between 1797 and 1819, Breadalbane’s piper developed a systematic written notation based on the flexible, vocal canntaireachd he knew only by ear. His final text, illustrated above, was never intended for the voice; some of his helpful signals for the eye are quite unsingable. The Campbell Canntaireachd is a visual code, the invention of an individual whose lack of exposure to colonial music education grants his scores a unique importance. Unlike later editors, Campbell had neither the wit nor inclination to sanitize his musical heritage. His father had studied a considerable period with Malcolm MacCrimmon and, according to Angus MacKay, ‘was esteemed a performer of merit’. No other source boasts such a close connection with the composers of the Gaelic agrarian high culture, save those of Joseph MacDonald and Niel MacLeod of Gesto.

An example of how notes were transcribed… The key note "Low A" is always represented in this notation by "in", probably a contraction of "An Dàra Aon", the second one, to distinguish the key note from the first note on the chanter—"low G". "High A" is always "i", but in a canntaireachd, it is often denoted by a preceding "l", thus "liu", and so confusion is avoided. "Low A" is either "in", "en", "em", or simply "n" after some notes. The alternatives seem to have been used for the sake of euphony.

An example of how grace notes were transcribed… Regarding grace notes, "h" the aspirate, qualifies all notes down to "low A", but often where "ha" obviously means "B" note, it must be concluded that it should be written "cha" (xa). Similarly "ho ho" should be "ho cho" (ho xo). The letter "d" is used, as is "t" to denote both "High G" and "D" grace notes, but an examination of the notation word, makes a mistake unlikely, thus "dieliu" means "F" with "high G" grace note, and then "high A" and "G". "Tihi" means two "E"s played with two "G" grace notes. "T" and "d" resemble each other very closely in Gaelic, but the context in canntaireachd makes it always easy to see whether "high G" grace note or "D" is meant. It is necessary to explain the compound grace note systems. "Dr" is doubling of "low G" by a touch of "D" grace note, and open "low A", and so on, over the whole scale. The letters "dr" are obviously a contraction of "dà uair", two times, or twice. "Trì" means doubling of "low G" by "D" grace note, and as "A" is opened, double "E" by "F" and "E" and open "E". This is a "Crunluath" form. "Tro" is the same, at first, but the doubling of "E" is done with the grips from "o" or the "C" note. This is "Crunluath-a-mach" (outer crunnluath). These examples will make the rest easy. In many tunes where the "tr" type appears, it obviously when translated should only have been a "dr" type, this confusion being only to the similarity of "d" and "t" in Gaelic.

Did you get that? And if that isn’t confusing enough, the single type of "tri-lugh" is composed of three "low A"s graced by "G", "D" and "E" gracenotes, and it precedes the note embellished. An example of this is "hininindo", the syllable "do" being "C" graced by "D". This type is called "fosgailte" (open), and is opposed by the double or closed form, represented by such a form as "hindirinto". The latter is called "a-steach" (inside), which is taken to a type like "hodorito", which is said to be "a-mach" (outside), as the grips are taken from the note played. The types last named are also "breabach" (kicking) forms, having a "kick” note at the finish. The "crun-lugh" or "ceithir-lugh" forms are also "fosgailte", "a-mach" and "a-steach". The word "hadatri" is "a-steach" when opposed to "hadatri" which is "a-mach". |