| This Week’s Topic… | |||

Best viewed in

|

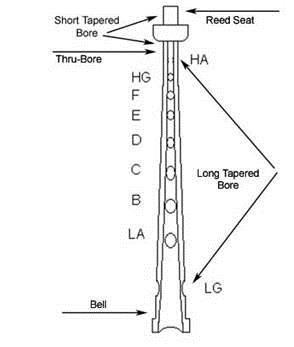

Chanter Basics

The note sounded by the chanter is

determined by which of its holes are covered (or not) by the piper's

fingers. Taping a note hole (we recommend pin striping tape) or

carving that note hole will adjust the pitch of the note however the

frequency (harmonics) is of internal origin and little can be done

to alter this. Some chanters have notes that do not harmonize with

the drone sound. These chanters will be very problematic and should

be avoided. Other chanters produce excellent harmonics throughout

and should be sought out. The pitch of individual notes can be

adjusted to suit the overall pitch you wish to play at and

note-to-note trueness.

How to set up a chanter Chanters should be assessed according to specific qualities in sound and performance. 1. Projection - Does the chanter "release" the sound or is it held close and muffled? Does the sound project evenly up and down the chanter? Is the top hand full, or does the sound get thin and faint? 2. Pitch - Is the overall chanter bright and exciting to play and listen to? Don't "force" the pitch by sinking the reed and distorting the balance between High A and Low A. Let the chanter play where it wants to. Overall the pitch should have spirit without being shrill? 3. Note-for-note is the chanter true? Are some notes excessively flat or sharp? 4. Harmonics - Is the sound rich with harmonics or is it bland? This is hard to explain however the chanter should produce a wide spectrum of harmonic frequencies that blend with the drone sound. 5. Stability - Notes should remain fairly stable with slight changes in blowing strength. Some chanters are less forgiving than others and notes may be inclined to change dramatically with small changes in blowing. Try to avoid these. There are additional factors that come into play. Your choice of reed will have a great bearing on what modifications you need to make to the chanter. Some makes of reeds are habitually flat or sharp on specific notes. You may get reeds that sound and behave differently from the same maker. You need to know how to cull these. Also, a reed that is broken-in will sound and behave differently than a new reed. Everybody blows a bagpipe just a bit differently. Very experienced pipers know exactly where to blow their pipes and how to hold them at that pitch. Less experienced or less skilled pipers will either overblow or underblow as a normal course of what they do and may also blow unevenly throughout a phrase or tune. I set my chanter with a solid balance between High A and Low A. I use a trusted reed that has been broken-in that has good response, good release, and lots of life. I play the pipes for 10 or 15 minutes to bring the reed up to pitch. I tune one or more drones to be in tune with High A and Low A. If necessary, I adjust the reed to achieve this balance. (Of course, a more experienced piper may choose to set his drones and the chanter to a different pitch. This will involve a keen ear, significant experience, greater patience, and potentially, more radical modifications to the chanter.) Then I listen carefully to the notes up and down the scale within the context of a simple tune. Robin Adair is an excellent place to start. The only note that isn't played in 16 bars of this tune is Low G. It gives you a pretty good place to start, especially with less experienced blowers. Green Hills is another good tune to play while setting your chanter. Whatever tune you pick, blow steady and listen for flat or sharp notes. If a note is sharp you can easily flatten the note by placing tape over the top of the note hole. Shift the tape up and down to get the note true. Where a note is flat, I modulate my blowing to get a sense of just how flat it is. If it's only slightly flat I may leave it and count on warm weather and adrenalin to brighten it up on the day. If it is solidly flat, then I enlarge the note hole. I use a Dremil tool to achieve an even and rounded or oval note hole. I start with a slight undercut at the top of the hole. I check often to test my progress. When I am satisfied that I have "carved" the flatness out of the note, I move to the next note until I've covered off the entire chanter. Touchups may be necessary during the process or at the end of the process. I may even want further touchups days or weeks later. It's all a matter of playing the reed and chanter to the point of perfection! |

||