| This Week’s Topic… | |||||||

Best viewed in

|

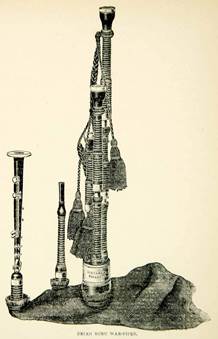

Irish Pipes

One famous description of the pipes from Richard Stanihurst's De Rebus Hibernicis (1586), reads as follows in English translation: “The Irish also use instead of a trumpet a wooden pipe constructed with the most ingenious skill to which a leather bag is attached with very closely plaited (or bound) leather bands. From the side of the skin issues a pipe through which as if through a tube the piper blows with swollen neck and distended cheeks, as it is filled with air the skin swells: when it swells he presses it down again with his arm. At this pressure two other wooden pipes, a shorter and a longer, emit a loud and piercing sound. There is also a fourth pipe, pierced with several holes which by opening and closing the holes with nimble fingers the piper manages to elicit from the upper pipes a loud or low sound as he thinks fit. The stem and stern of the whole affair is that the wind should have no outlet through any part of the bag except the mouths of the pipes. For if anyone (as is the practice of merrymakers when they want to give annoyance to these pipers) make even a pinhole in the skin the instrument is done for because the bag collapses. This sort of instrument is held among the Irish to be a whetstone for martial courage: for just as other soldiers are stirred by the sound of trumpets, so they are hotly stimulated to battle by the noise of this affair.” The pipes seem to have figured prominently in the war with William of Orange. When the exiled King James II arrived in Cork City in March 1689, he was greeted with “bagpipes and dancing, throwing their mantles under his horse’s feet”. On his way to the castle in Dublin, “the pipers of the several companies played the Tune of The King enjoys his own again”. In the second half of the 19th century, however, the general revival of Irish nationalism and Gaelic culture seems to have coincided with a return of the popularity of the warpipes. The art picked up again until the pipes achieved considerable popularity in both military and civilian use. Today, pipe bands of the same kind as the known Highland form are a standard feature of British regiments with Irish honors and the Irish Armed Forces, and there are many local bands throughout both the Republic and Northern Ireland. The Irish warpipes as played today are one and the same with the Scottish Highland bagpipe. Attempts in the past to make a distinct instrument for Irish pipers have not proven popular in the long run.

The earliest surviving sets of uilleann pipes date from the second half of the 18th century, but it must be said that datings are not definitive. Only recently has scientific attention begun to be paid to the instrument, and problems relating to various stages of its development have yet to be resolved. It is gradually becoming accepted that the union pipes originated from the Pastoral pipes and gained popularity in Ireland within the Protestant Anglo-Irish community and its gentlemen pipers. Certainly many of the early players in Ireland were Protestant, possibly the best known being the mid-18th century piper Jackson from Co Limerick and the 18th century Tandragee pipemaker William Kennedy. The pipes were certainly often used by the Protestant clergy, who employed them as an alternative to the church organ. As late as the 19th century the instrument was still commonly associated with the Anglo-Irish, e.g. the Anglican clergyman Canon James Goodman (1828–1896) from Kerry, who interestingly had his uilleann pipes buried with him at Creagh (Church of Ireland) cemetery near Baltimore, County Cork. His friend, and Trinity College colleague, John Hingston from Skibbereen also played the uilleann pipes. The bag of the uilleann pipes is inflated by means of a small set of bellows strapped around the waist and the right arm (in the case of a right-handed player; in the case of a left-handed player the location and orientation of all components are reversed). The bellows not only relieve the player from the effort needed to blow into a bag to maintain pressure, they also allow relatively dry air to power the reeds, reducing the adverse effects of moisture on tuning and longevity. Some pipers can converse or sing while playing. The uilleann pipes are distinguished from many other forms of bagpipes by their tone and wide range of notes – the chanter has a range of two full octaves, including sharps and flats – together with the unique blend of chanter, drones, and regulators. The regulators are equipped with closed keys that can be opened by the piper's wrist action enabling the piper to play simple chords, giving a rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment as needed. There are also many ornaments based on multiple or single grace notes. The chanter can also be played staccato by resting the bottom of the chanter on the piper's thigh to close off the bottom hole and then open and close only the tone holes required. If one tone hole is closed before the next one is opened, a staccato effect can be created because the sound stops completely when no air can escape at all.

|

||||||