|

|

Best viewed in

|

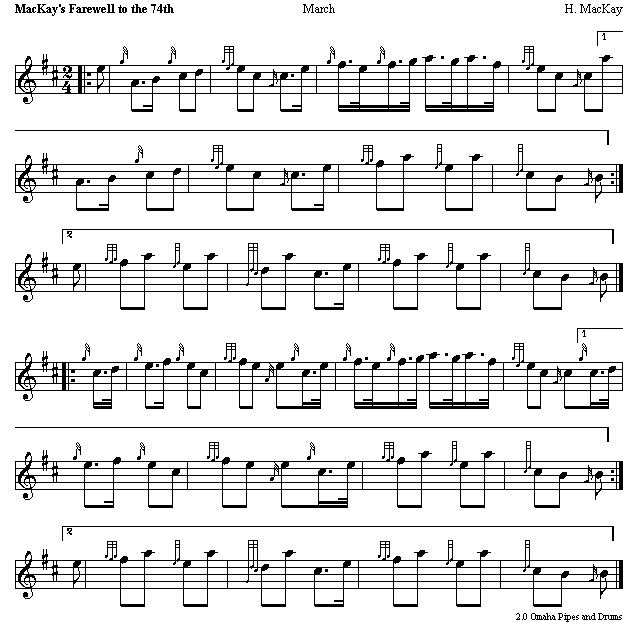

The MacKays are believed to descend from the Picts, ancient tribes that lived in Scotland. The name Mackay is also found in Ireland from ancient times, when several tribes from the northern area of Ireland, which was once part of an ancient Scottish kingdom known as Dál Riata, moved across the sea to Scotland. The MacKays in Scotland were based in Strathnaver in modern Sutherland. Although the exact origin of Clan MacKay is unknown, it is generally accepted that they belonged to the early Celtic population of Scotland, although, given their geographical proximity to the Norse immigrants, it is likely that the two races later intermarried. They were a powerful force in politics beginning in the 14th century, supporting Robert the Bruce. In the centuries that followed they were anti-Jacobite. The Highland Clearances had dire consequences for the clan, but since then they have spread through many parts of the world and have provided it many famous and influential people. The territory of the Clan MacKay consisted of the parishes of Durness, Tongue and Farr in the north of the county of Sutherland, later it would extend and include the parish of Reay in the west of the neighboring county of Caithness. The chief of the clan is Lord Reay. There have been numerous MacKay pipers. Gairloch is the ancestral home of the MacKenzies of Gairloch. Hereditary pipers to the MacKenzies were the MacKays who came from Sutherland. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries these MacKay pipers were almost as celebrated as the MacCummons of Skye. The first of the MacKay pipers for the MacKenzies was Ruairidh. Ruairidh was over sixty when his only son, Iain, was born. When he was seven years old, Iain lost his eyesight after contracting smallpox. Iain was a piper of renown and became known as Iain Dall (Blind John) or Am Piobair Dall (The Blind Piper). At an early age he was sent to the MacCummon College of Piping at Dunvegan in Skye. Jealous of the Blind Piper's skill, pupils of the college planned to kill him. They chased him over a rock causing him to fall between twenty and thirty feet below. Miraculously he escaped serious injury. Iain Dall was piper to Sir Kenneth MacKenzie, the first baronet of Gairloch. He was a gifted poet as well as a piper. He had the rare distinction of combining the office of bard with that of piper. Iain Dall's stature in the Gaelic music world was immense and the stories of his skill are still repeated. His compositions of ceol more (great music) and ceol bag (little music) were not written down until after his death. When he died at the age of ninety, his only son Angus succeeded him as MacKenzie's hereditary piper. One story told of Angus is that there was to be a great competition in Edinburgh. Angus was expected to win. As there was always jealously among pipers, just before the competition was to begin, one of his rivals pierced his pipe bag with a knife. A friend whose name was Mary came to his aid by finding him an undressed sheep skin. Working throughout the night, Angus fashioned it into a bag for his pipes. The next day he won the competition and later composed the well-known piobaireachd Maladh Mairi (Mary's Praise for Her Gift). The last of these Gairloch pipers was John, son of Angus. He had a very large family - ten daughters (three of whom were married) and two sons. Their family moved to Nova Scotia. A John MacKay was pipe major of the King's Own Borderers from 1856 - 1869 after transferring from the 78th Regiment; he is known for a number of pipe tunes. Angus MacKay pioneered the art of putting pipe music on paper. Kenneth MacKay, piper in the 79th Highlanders, earned immortal fame by playing the piobaireachd Cogra no Geth ('Peace or War') round the squares between the charges of the French Cavalry during the Battle of Waterloo. Kenneth was presented with a set of Silver Pipes by the King's own hand for his bravery. And on and on and on. The MacKay pipers are legendary. Campbell had held a commission in the old 78th, or Fraser's Highlanders during the French and Indian War. Most regimental officers were commissioned in 1777, but the first muster of the regiment was not held until April 1778. It was inspected at Glasgow in May 1778 and sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia, in August 1778. The regiment's flank companies (the grenadier and light infantry companies) joined the main British army in New York in the spring of 1779, while the remainder of the regiment moved to Bagaduce in Massachusetts (now the town of Castine, Maine). The regiment, together with a detachment of the 82nd Regiment of Foot, began construction of a post to be called Fort George, which they held through July and early August against attacks by an American expeditionary force from Massachusetts under Commodore Dudley Saltonstall and General Solomon Lovell. On 13 August, a relief force of British ships arrived from New York under the command of Commodore Sir George Collier, and the Americans gave up their siege and withdrew. The regiment remained at Fort George until January 1784, when the fort was evacuated and the troops returned to Halifax. There they were reunited with the regiment's flank companies; these had served with General Sir Henry Clinton in South Carolina in 1779 and 1780. The Light Company had also served in Virginia in 1781, ending as part of Lord Cornwallis' army that had surrendered at Yorktown in October 1781 and remaining as prisoners until the end of the war in 1783, when they had returned to New York. The regiment, now complete, returned to Great Britain in 1784, landing at Portsmouth and marching from there to Stirling, where it was disbanded on 24 May 1784. A set of bagpipes, believed to have been played at the mustering of the regiment in 1778 by one Piper MacCorquodale are in the collection of the National Museums of Scotland.

|