| This Week’s Topic… | |||

Best viewed in

|

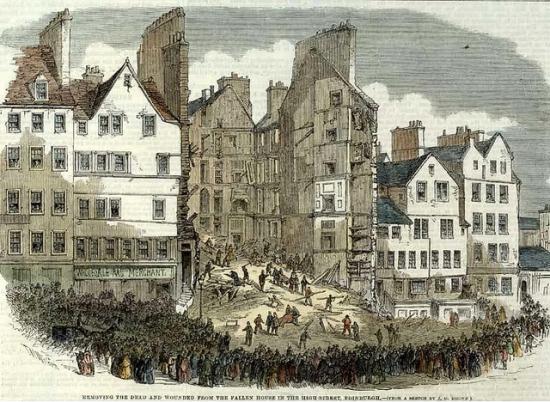

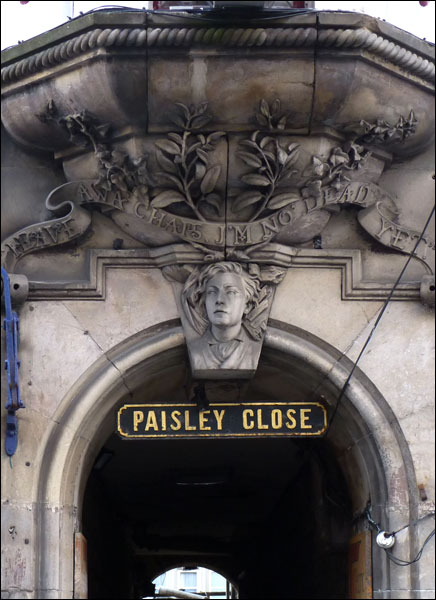

Paisley Close The Old Town of Edinburgh consisted originally of the main street, now known as the Royal Mile, and the small alleyways and courtyards that led off it to the north and south. These were usually named after a memorable occupant of one of the apartments reached by the common entrance, or a trade plied by one or more residents. Generically such an alleyway is termed a close /ˈkloʊs/, a Scots term for alleyway, although it may be individually named close, entry, court, or wynd. A close is private property, hence gated and closed to the public, whereas a wynd is an open thoroughfare, usually wide enough for a horse and cart. Most slope steeply down from the Royal Mile creating the impression of a herring-bone pattern formed by the main street and side streets when viewed on a map. Many have steps and long flights of stairs. Because of the need for security within its town walls against English attacks in past wars, Edinburgh experienced a pronounced density in housing. Closes tend to be narrow with tall buildings on both sides, giving them a canyon-like appearance and atmosphere. The Royal Mile comprises four, linear, conjoined streets: Castle Hill; Lawnmarket; High Street; and Canongate. Closes are listed below from west to east, divided between the south and north sides of the street. The High Street runs from St Giles Street to St Mary's Street, the location of the Netherbow Port, and the limit of the pre-19th century burgh of Edinburgh. Paisley Close is a dead end on the north side of High Street. Paisley (Paisley's) Close was named thus by 1679 for Henry Paisley, who owned property in it. On the Sunday morning of November 24th, 1861, the adjacent 250-year-old tenement in Bailie Fyfe's Close collapsed, killing thirty five people.

In 1867 the City Improvement Act was passed, beginning the gradual dismantling of the Old Town's medieval closes and wynds which, but the end of the 19th Century, had been almost entirely replaced by the sturdier Victorian buildings which make up the bulk of the historic "Old Town" today; ironically making it less old, brick-for-brick, than the "New Town". Among them was the new block over Paisley Close, the lintel of which bears a bust of Joseph McIvor, though "my lads" was replaced by the more genteel "chaps". The expansion of the city limits gradually eased the overcrowding and led, eventually, to the elimination of the Old Town's slums.

|

||