Best viewed in

Internet Explorer

PDF

Back to

Updated

07/17/2017 |

The Siege of Leith

In

1560, a siege of Leith by an English army – against the occupying French

– marked both the end of the ‘Auld Alliance’ that had been in place for

265 years and the establishment of the Protestant religion in Scotland.

James V died in 1542, days after his army was routed by the English at

Solway Moss, leaving his new-born daughter Mary as his heir and the Earl

of Arran as Regent. The late king’s widow, Mary of Guise, kept control

of their daughter. The vacillating Arran was soon facing armed challenge

to his leadership, as well as trying to balance the aspirations of the

queen for a French alliance and a faction of Protestant lords wanting

rapprochement with England.

Advised by the astute Cardinal Beaton, the queen waged a skillful

campaign to preserve the Roman Catholic religion. The church had long

been corrupt and controlled half the wealth of the nation. Reformers had

been working in Scotland since the 1520s and had gradually built up

popular support. The dissolution of the monasteries in England after

Henry VIII declared himself head of the church and the parceling out of

their land to the aristocracy led much of the Scots nobility to become

enthusiastic supporters of reform. Beaton and Mary were in favor of an

alliance with France, which was also at war with England; the reformers

wanted closer ties with England and, particularly, its wealth.

King Henry wished the infant Mary to marry his son, but the Catholic

faction, with the support of the parliament, preferred a French union.

So English armies rolled north in what came to be called the ‘Rough

Wooing,’ creating mayhem in much of Scotland. After the assassination of

Beaton in 1546, the campaign culminated in the battle of Pinkie Cleugh

in 1547, which cost up to 15,000 Scots lives against 2,600 English.

The critical national situation quelled the dissent of the pro-English

faction of Reformers and strengthened the hand of Mary of Guise. France

had already sent troops to help Scotland and now 10,000 of their

soldiers landed at the port of Leith and fortified the town. The infant

queen was sent to France and betrothed to the Dauphin in August 1548.

The regent Arran was created Duke of Chatelherault by Henry II of France

for arranging the French marriage and in 1555 he handed the regency over

to Mary, who ran the country with the help of French advisers. They were

quite popular, but the Protestant magnates were resentful of their power

and influence. Declaring themselves to be the Lords of the Congregation

and allying themselves with John Knox, they deprived Mary of the regency

and raised an army of 12,000 to expel the French. They soon controlled

the Lowlands and Edinburgh, but Mary retook Edinburgh and settled in the

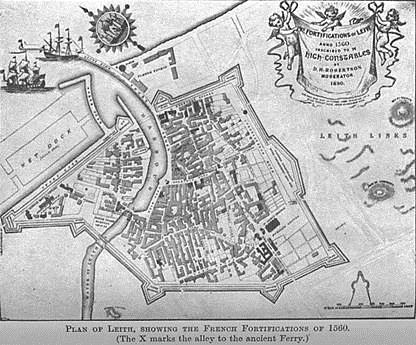

castle. Her troops continued to fortify Leith, enclosing about 90 acres

with huge earth ramparts and bastions.

In October 1559, the Lords of the Congregation blockaded the town. They

built ladders to scale its defenses and mounted an assault. The ladders

were too short and the attack was easily repulsed. The ladders had been

built in St Giles church – an impious use of the building – and the Lord

consequently had frowned upon the enterprise. The Scots army was unpaid,

lacked much interest in a battle and was no match for the 3,000

experienced French soldiers who sallied out from behind their earth

ramparts to plunder for provisions and launch small-scale attacks.

The Lords of the Congregation asked for help from the newly crowned

Queen Elizabeth. In 1560, at the beginning of April, 6,000 troops and

artillery arrived and the English fleet sealed the port. The English

raised mounds round the fortifications for their guns and began to

bombard the town. They succeeded in knocking down the steeple of St

Anthony’s church, on top of which the French had winched a cannon. The

French commanders were celebrating Easter mass in South Leith Parish

Church. During the service a cannonball passed harmlessly in through a

window and out of the church door.

The French continued to make damaging sallies; many such skirmishes took

place on Leith Links in full view of the opposing commanders so they

were desperate affairs as each side sought to prove its gallantry.

A major assault with more than 5,000 men was launched against the town

on May 7th. Once again the ladders were too short and it was

repulsed with a loss of 1500 men. The French lost less than 20. It was

reported that the ramparts were defended by women hurling rocks down on

the attackers and supplying the men with ammunition. The Frenchmen’s

harlots were of the most part Scotch strumpets, remarked John Knox. As

the siege continued, provisions within Leith were running very low. They

were eating horses and harvesting weeds from the ramparts.

Then, on the June 11th, Mary of Guise died at the castle. She

was known to be suffering from dropsy – heart failure – but her death

had not been expected. She was the reason that the French were in

Scotland and so a truce was arranged. On June 20th, the

opposing sides feasted together on the beach. The English brought beef,

bacon, poultry, wine and beer, the French cold roast chickens, a horse

pie and six roast rats.

The hostilities were officially ended by the Treaty of Edinburgh signed

on July 7th in the names of Elizabeth, Queen of England, and

Francois and Mary, King and Queen of France and Scotland. The French and

English troops left Scotland and the Edinburgh town treasury had to pay

for clearing up the mess they left behind.

During the following month, the Scots parliament abolished the

jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Church and instituted the Reformed

Confession of Faith drawn up by John Knox and his colleagues. A year

later the Catholic Queen Mary, by then a 19 year-old widow, landed at

Leith to take up her kingdom, the most fiercely Protestant nation in

Europe. The siege of

Leith has to a certain extent been forgotten and regarded as just

another incident in an eventful and bloody period of Scottish history

however it has great significance. For one thing it was the first time

that Scotland and England fought side by side. It could also be

considered as the last significant foreign occupation of the British

mainland and marked and end to both the alliance with France and the

catholic domination of Scotland. |