| This Week’s Topic… | |||

Best viewed in

|

|

||

| After

Omdurman, veteran war correspondent Bennet Burleigh described the

courage of the Mahdists, writing ‘Few will ever see again so great and

brave a show. A vast army, with a front of three miles, covering an

undulating plain – warriors mounted and a-foot, clad in quaint and

picturesque drapery, with gorgeous barbaric display of banners,

burnished metal, and sheen of steel – came sweeping upon us with the

speed of cavalry. Half-a-dozen batteries smote them, a score of Maxims

and 10,000 rifles unceasingly buffeted them, making great gaps and

rendering their ranks in all directions. With magnificent courage,

without pause, the survivors invariably drew together, furiously,

frenziedly running to cross steel with us. Their mad devotion won

admiration on all sides as in our own ranks.’ Macdonald distinguished

himself as a tactician, but had things not worked out in his favor,

history might have remembered him less favorably – for he had ignored a

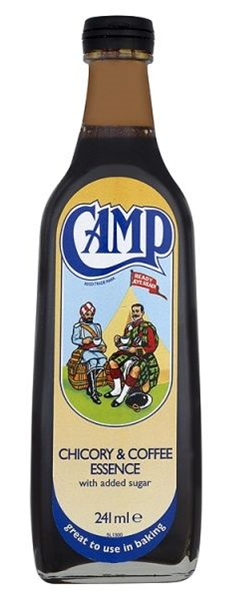

direct order from his divisional commander! ‘Fighting Mac’ was cornered and, as Bennet Burleigh recounted in his book Khartoum Campaign 1898, of the Re-Conquest of the Soudan, his action was ‘the most brilliant and heroic episode of a day so full of glowing incident.’ ‘The nature of the ground,’ wrote Burleigh, ‘forced some of them out of their true relative positions. Macdonald had marched out due west. The dervishes, like wolves upon the scent for prey, suddenly sprang from unexpected lairs. With swifter feet and fiercer courage than ever, they dashed for the comparatively isolated brigade of Colonel Macdonald... No force could have been in time to save them had they not fought and saved themselves… Indecision or flurry would have totally wrecked Macdonald’s brigade, but happily their brigadier knew well his business. An order was sent to him which had it been obeyed, would have ensured inevitable disaster to the brigade, if not a catastrophe to the army. He was bade to retire... Macdonald knew better than to attempt a retrograde movement in the face of so fleet and daring a foe. It would have spelled annihilation. The sturdy Highlandman said ‘I’ll no do it. I’ll see them d–––––d first. We maun just fight.’ And fight, they did. Macdonald’s brigade lost 128 men out of a total British, Egyptian and Sudanese loss of just over 500. An estimated 15,000 Mahdists had been slain. After the conflict was over, medals and honors were heaped upon the generals, but Fighting Mac’s contribution was not recognized. Burleigh noted that ‘In the Scotch press, and particularly in that of the Far North, there has been much adverse comment about the ungenerous treatment accorded their countryman. The Highlanders, as is their nature, write and speak passionately of the matter, and pertinently ask if the authorities wish no more Highland recruits.’ Hector Macdonald had enemies, amongst them those who disapproved of anyone rising from the ranks to colonel. What they made of his eventual promotion to Major-General and later knighthood is probably not printable. There were others amongst the British officer corps who claimed they couldn’t understand what he said – he had been brought up a Gaelic speaker, and spoke English with a thick Highland accent. So it was appropriate in many ways, but a surprise to his rivals, that he was given the command of the Highland Brigade during the Boer War. After the cessation of the Boer War, he was made commander of British forces in Ceylon – now Sri Lanka – where rumors started to circulate about his sexuality. On his way back from London to Ceylon in 1903 to face a court martial, he read a lurid account of the allegations against him in a newspaper, and shot himself in his Paris hotel room. An official inquiry into his death found no evidence to support the accusations and noted that ‘we firmly believe the cause which gave rise to the inhuman and cruel suggestions of crime were prompted through vulgar feelings of spite and jealousy in his rising to such a high rank of distinction in the British Army.’ Had he been an establishment figure rather than a highland crofter’s son, he might have been treated very differently. He remained a legendary figure in the eyes of the public, and just like Elvis, his enduring fame was such that sightings of him were reported long after his death – across the Far East and well into the Great War years. But Hector Archibald Macdonald’s story doesn’t end there. On the original Camp Coffee bottle, he was shown seated on a drum, being served coffee on a tray by a Sikh batman. By the late 1990s, the ‘political correctness’ brigade saw racist overtones in the label, and at a stroke, the relationship between sergeant-major and batman were airbrushed out of history. Patersons were persuaded to change the illustration – the tray of coffee was moved to a table, the Sikh soldier left standing purposeless alongside the seated soldier. Even that was eventually considered sufficiently offensive and was changed yet again so that the Sikh and the Highlander were seated together as equals. |

|||